Regular script

| Regular script |

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Type | |

| Languages | Old Chinese, Middle Chinese, Modern Chinese |

|

Time period

|

Bronze Age China, Iron Age China, Present day |

|

Parent systems

|

Oracle Bone Script

|

|

Child systems

|

Kanji Kana Hanja Zhuyin Simplified Chinese Chu Nom Khitan script Jurchen script Tangut script Nü Shu |

| 4E00–9FFF, 3400–4DBF, 20000–2A6DF, 2A700–2B734, 2F00–2FDF, F900–FAFF | |

| Regular script | |||||||||||||||||

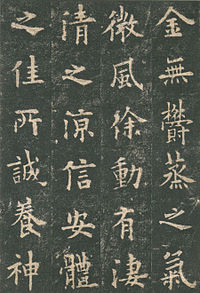

Chinese characters of "Regular Script" in traditional characters (left) and in the simplified form (right).

|

|||||||||||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 楷書 | ||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Simplified Chinese | 楷书 | ||||||||||||||||

| Literal meaning | model script | ||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||

| Alternative Chinese name | |||||||||||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 真書 | ||||||||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 真书 | ||||||||||||||||

| Literal meaning | real script | ||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||

| Second alternative Chinese name | |||||||||||||||||

| Chinese | 正楷 | ||||||||||||||||

| Literal meaning | correct model | ||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||

| Third alternative Chinese name | |||||||||||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 楷體 | ||||||||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 楷体 | ||||||||||||||||

| Literal meaning | model form | ||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||

| Fourth alternative Chinese name | |||||||||||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 正書 | ||||||||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 正书 | ||||||||||||||||

| Literal meaning | correct script | ||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||

| Transcriptions | |

|---|---|

| Standard Mandarin | |

| Hanyu Pinyin | kǎishū |

| Wade–Giles | k'ai3-shu1 |

| Yue: Cantonese | |

| Yale Romanization | kaái syū |

| Jyutping | kaai² syu¹ |

| Canton Romanization | kai² xu¹ |

| Transcriptions | |

|---|---|

| Standard Mandarin | |

| Hanyu Pinyin | zhēnshū |

| Wade–Giles | chên1-shu1 |

| Yue: Cantonese | |

| Yale Romanization | jān syū |

| Jyutping | zan¹ syu¹ |

| Canton Romanization | zen¹ xu¹ |

| Transcriptions | |

|---|---|

| Standard Mandarin | |

| Hanyu Pinyin | zhèngkǎi |

| Wade–Giles | chêng4-k'ai3 |

| Yue: Cantonese | |

| Yale Romanization | jing kaái |

| Jyutping | zing³ kaai² |

| Canton Romanization | jing³ kai² |

| Transcriptions | |

|---|---|

| Standard Mandarin | |

| Hanyu Pinyin | kǎitǐ |

| Wade–Giles | k'ai3-t'i3 |

| Yue: Cantonese | |

| Yale Romanization | kaái tái |

| Jyutping | kaai² tai² |

| Canton Romanization | kai² tei² |

| Transcriptions | |

|---|---|

| Standard Mandarin | |

| Hanyu Pinyin | zhèngshū |

| Wade–Giles | chêng4-shu1 |

| Yue: Cantonese | |

| Yale Romanization | jing syū |

| Jyutping | zing³ syu¹ |

| Canton Romanization | jing³ xu¹ |

Regular script (traditional Chinese: 楷書; simplified Chinese: 楷书; pinyin: kǎishū; Hepburn: kaisho), also called 正楷 (pinyin: zhèngkǎi), 真書 (zhēnshū), 楷體 (kǎitǐ) and 正書 (zhèngshū), is the newest of the Chinese script styles (appearing by the Cao Wei dynasty ca. 200 CE and maturing stylistically around the 7th century), hence most common in modern writings and publications (after the Ming and gothic styles, used exclusively in print).

Regular script came into being between the Eastern Hàn and Cáo Wèi dynasties, and its first known master was Zhōng Yáo (sometimes also read Zhōng Yóu; 鍾繇), who lived in the E. Hàn to Cáo Wèi period, ca. 151–230 CE. He is known as the “father of regular script”, and his famous works include the Xuānshì Biǎo (宣示表), Jiànjìzhí Biǎo (薦季直表), and Lìmìng Biǎo (力命表). Qiu Xigui describes the script in Zhong’s Xuānshì Biǎo as:

…clearly emerging from the womb of early period semi-cursive script. If one were to write the tidily written variety of early period semi-cursive script in a more dignified fashion and were to use consistently the pause technique (dùn 頓, used to reinforce the beginning or ending of a stroke) when ending horizontal strokes, a practice which already appears in early period semi-cursive script, and further were to make use of right-falling strokes with thick feet, the result would be a style of calligraphy like that in the "Xuān shì biǎo".

However, other than a few literati, very few wrote in this script at the time; most continued writing in neo-clerical script, or a hybrid form of semi-cursive and neo-clerical. Regular script did not become dominant until the early Southern and Northern Dynasties, in the 5th century; this was a variety of regular script which emerged from neo-clerical as well as from Zhong Yao's regular script, and is called "Wei regular" (魏楷 Weikai). Thus, regular script has parentage in early semi-cursive as well as neo-clerical scripts.

...

Wikipedia