Antoin Sevruguin

| Antoin Sevruguin | |

|---|---|

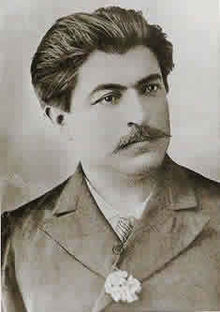

Antoin Sevruguin in Vienna. Photo taken before 1880

|

|

| Born | 1830 Russian Embassy Tehran, Iran |

| Died | 1933 Tehran, Iran |

| Known for | Painting, Photography |

| Patron(s) | Naser al-Din Shah |

Antoin Sevruguin (Persian: آنتوان سورگین; 1830-1933) was a photographer in Iran during the reign of the Qajar dynasty (1785–1925).

Born into a Russian family of Armenian-Georgian origin in the Russian embassy of Tehran, Iran: Antoin Sevruguin was one of the many children of Vasily Sevryugin and a Georgian Achin Khanoum. Vasily Sevryugin was a Russian diplomat to Tehran. Achin had raised her children in Tbilisi, Georgia, because she was denied her husband’s pension. After Vassil died in a horse riding accident Antoin gave up the art form of painting, and took up photography to support his family. His brothers Kolia and Emanuel helped him set up a studio in Tehran on Ala al-dawla Street (today Ferdowsi St.).

Many of Antoin’s photographs were taken from 1870-1930. Because Sevruguin spoke Persian as well as other languages, he was capable of communicating to different social strata and tribes from his country Iran. His photos of the royal court, harems, and mosques and other religious monuments were compared to the other Western photographers in Persia. The reigning Shah, Nasir al-Din Shah (reigned from 1846–1896) took a special interest in photography and many royal buildings and events were portrayed by Sevruguin.

Because Sevruguin travelled Persia and took pictures of the country, his travels record the Iran as it was in his time. Sevruguins pictures show Tehran as a small city. They show monuments, bridges and landscapes which have changed since then.

Some of Sevruguin's portraiture fed preexisting stereotypes of Easterners but nevertheless had a commercial value and today prove to be historical records of regional dress. Photographic studios in the nineteenth century advertised a type of picture known in French as "types". These were portraits of typical ethnic groups and their occupation. They informed the European viewer, unfamiliar with Persian culture, about the looks of regional dress, handcraft, religion and professions. Photographing regional costumes was an accepted method of ethnological research in the nineteenth century. Many European ethnological museums bought Sevruguins portraiture to complement their scientific collection. Museums collected pictures of merchants in the bazaar, members of a zurkhana (a wrestling school), dervishes, gatherings of crowds to see the taziyeh theatre, people engaged in shiite rituals and more. Sevruguins portraits were also spread as postcards with the text: 'Types persans'. Sevruguin was a photographer who had no boundaries in portraying people of all sorts of social classes and ethnic backgrounds. He portrayed members of the Persian royal family as well as beggars, fellow countrymen of Iran or Westerners, farmers working fields, womenweavers at work, army officers, religious officials, Zoroastrians, Armenians, Lurs, Georgians, Kurds, Shasavan, Assyrians, and Gilak.

...

Wikipedia