The Merry Devil of Edmonton

| The Merry Devil of Edmonton | |

|---|---|

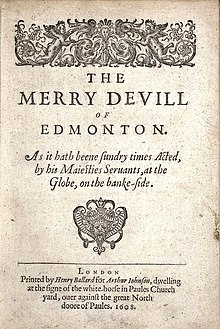

Title page of the 1608 edition of The Merry Devil of Edmonton

|

|

| Date premiered | 1600-1604 |

| Original language | English |

| Genre | Comedy |

The Merry Devil of Edmonton is an Elizabethan-era stage play; a comedy about a magician, Peter Fabell, nicknamed the Merry Devil. It was at one point attributed to William Shakespeare, but is now considered part of the Shakespeare Apocrypha.

Scholars have conjectured dates of authorship for the play as early as 1592, though most favor a date in the 1600–4 period.The Merry Devil enters the historical record in 1604, when it is mentioned in a contemporary work called the Black Booke. The play was entered into the Stationers' Register on 22 October 1607, and published the next year, in a quarto printed by Henry Ballard for the bookseller Arthur Johnson (Q1 – 1608). Five more quartos appeared through the remainder of the century: Q2 – 1612; Q3 – 1617; Q4 – 1626; Q5 – 1631; and Q6 – 1655. All of these quartos were anonymous.

Publisher Humphrey Moseley obtained the rights to the play and re-registered it on 9 September 1653 as a work by William Shakespeare. Moseley's attribution to Shakespeare was repeated by Edward Archer in his 1656 play list [see: The Old Law], and by Francis Kirkman in his list of 1661. The play was bound with Fair Em and Mucedorus in a book titled "Shakespeare. Vol. I" in the library of Charles II.

As its publishing history indicates, the play was popular with audiences; it is mentioned by Ben Jonson in the Prologue to his play The Devil is an Ass. While Merry Devil was a King's Men play and Shakespeare may have had a minor role in its creation, it does not have the distinctive marks of Shakespeare's style. Individual 19th-century critics attempted to attribute the play to Michael Drayton or to Thomas Heywood; but their attributions have not been judged credible by other scholars. William Amos Abrams proposed Thomas Dekker as the play's author in his 1942 edition; Dekker scholars Gerald J. Eberle and M. T. Jones-Davies agreed, though Fredson Bowers, the editor of Dekker's Dramatic Works, was unpersuaded by the evidence offered and did not include it in his edition.

...

Wikipedia