Shanghai Ghetto

| Shanghai Ghetto | |||||||||

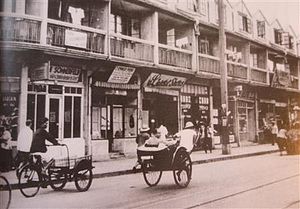

Seward Road in the ghetto in 1943

|

|||||||||

| Chinese name | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chinese | 上海隔都 | ||||||||

|

|||||||||

| Restricted Sector for Stateless Refugees | |||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 無國籍難民限定地區 | ||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 无国籍难民限定地区 | ||||||||

|

|||||||||

| Japanese name | |||||||||

| Kanji | 無国籍難民限定地区 | ||||||||

| Transcriptions | |

|---|---|

| Standard Mandarin | |

| Hanyu Pinyin | Shànghǎi gédōu |

| Wade–Giles | Shang4-hai3 ko2-tou1 |

| Transcriptions | |

|---|---|

| Standard Mandarin | |

| Hanyu Pinyin | Wú guójí nànmín xiàndìng dìqū |

| Wade–Giles | Wu2 kuo2-chi2 nan4-min2 hsien4-ting4 ti4-ch'ü1 |

The Shanghai Ghetto, formally known as the Restricted Sector for Stateless Refugees, was an area of approximately one square mile in the Hongkew district of Japanese-occupied Shanghai (the southern Hongkou and southwestern Yangpu districts of modern Shanghai). The area included the community around the Ohel Moshe Synagogue but about 23,000 of the city's Jewish refugees were restricted or relocated to the area from 1941 to 1945 by the Proclamation Concerning Restriction of Residence and Business of Stateless Refugees. It was one of the poorest and most crowded areas of the city. Local Jewish families and American Jewish charities aided them with shelter, food, and clothing. The Japanese authorities increasingly stepped up restrictions, but the ghetto was not walled, and the local Chinese residents, whose living conditions were often as bad, did not leave.

At the end of the 1920s, most German Jews were loyal to Germany, assimilated and relatively prosperous. They served in the German army and contributed to every field of German science, business and culture. After the Nazis were elected to power in 1933, the state-sponsored anti-Semitic persecution such as the Nuremberg Laws (1935) and the Kristallnacht (1938) drove masses of German Jews to seek asylum abroad, but as Chaim Weizmann wrote in 1936, "The world seemed to be divided into two parts—those places where the Jews could not live and those where they could not enter."

The Evian Conference demonstrated that by the end of the 1930s it was almost impossible to find a destination open for Jewish immigration.

According to Dana Janklowicz-Mann:

Jewish men were being picked up and put into concentration camps. They were told you have X amount of time to leave—two weeks, a month—if you can find a country that will take you. Outside, their wives and friends were struggling to get a passport, a visa, anything to help them get out. But embassies were closing their doors all over, and countries, including the United States, were closing their borders. ... It started as a rumor in Vienna... ‘There’s a place you can go where you don’t need a visa. They have free entry.’ It just spread like fire and whoever could, went for it.

...

Wikipedia