Gaeilgeoir

| Irish | |

|---|---|

| Gaeilge | |

"Gaelach" in traditional Gaelic type

|

|

| Pronunciation | [ˈɡeːlʲɟə] |

| Native to | Ireland |

| Region | Ireland, mainly Gaeltacht |

|

Native speakers

|

74,000 in Ireland (2016) L2 speakers: 1,761,420 in Republic of Ireland (2016), 104,943 in Northern Ireland (2011) Total: 1,154,923 (17.57% of Ireland (NI & Republic)) |

|

Early forms

|

|

|

Standard forms

|

An Caighdeán Oifigiúil |

|

Latin (Irish alphabet) Irish Braille |

|

| Official status | |

|

Official language in

|

|

|

Recognised minority

language in |

|

| Regulated by | Foras na Gaeilge |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-1 | ga |

| ISO 639-2 | |

| ISO 639-3 | |

| Glottolog | iris1253 |

| Linguasphere | 50-AAA |

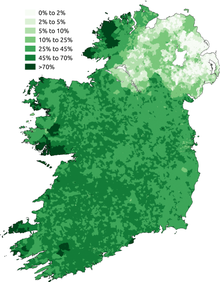

Proportion of respondents who said they could speak Irish in the Republic of Ireland and Northern Ireland censuses of 2011.

|

|

Irish (Gaeilge), also referred to as Gaelic or Irish Gaelic, is a Goidelic language of the Indo-European language family originating in Ireland and historically spoken by the Irish people. Irish is spoken as a first language by a small minority of Irish people, and as a second language by a larger group of non-native speakers. Irish enjoys constitutional status as the national and first official language of the Republic of Ireland, and is an officially recognised minority language in Northern Ireland. It is also among the official languages of the European Union. The public body Foras na Gaeilge is responsible for the promotion of the language throughout the island of Ireland.

Irish was the predominant language of the Irish people for most of their recorded history, and they brought it with them to other regions, notably Scotland and the Isle of Man, where Middle Irish gave rise to Scottish Gaelic and Manx respectively. It has the oldest vernacular literature in Western Europe.

The fate of the language was influenced by the increasing power of the English state in Ireland. Elizabethan officials viewed the use of Irish unfavourably, as being a threat to all things English in Ireland. Its decline began under English rule in the 17th century. In the latter part of the 19th century, there was a dramatic decrease in the number of speakers, beginning after the Great Famine of 1845–52 (when Ireland lost 20–25% of its population either to emigration or death). Irish-speaking areas were hit especially hard. By the end of British rule, the language was spoken by less than 15% of the national population. Since then, Irish speakers have been in the minority. Efforts have been made by the state, individuals and organisations to preserve, promote and revive the language, but with mixed results.

...

Wikipedia