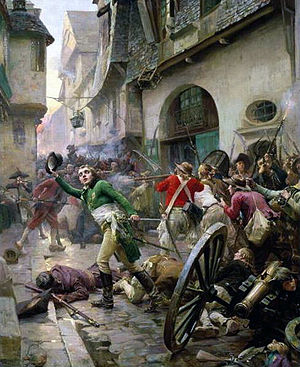

Revolt in the Vendée

Supported by:

The War in the Vendée (1793 to 1796; French: Guerre de Vendée) was an uprising in the Vendée region of France during the French Revolution. The Vendée is a coastal region, located immediately south of the Loire River in western France. Initially, the war was similar to the 14th-century Jacquerie peasant uprising, but quickly acquired themes considered by the government in Paris to be counter-revolutionary, and Royalist. The uprising headed by the self-styled Catholic and Royal Army was comparable to the Chouannerie, which took place in the area north of the Loire.

The departments included in the uprising, called the Vendée Militaire, included the area between the Loire and the Layon rivers: Vendée (Marais, Bocage Vendéen, Collines Vendéennes), part of Maine-et-Loire west of the Layon, and the portion of Deux Sèvres west of the River Thouet. Having secured their pays, the deficiencies of the Vendean army became more apparent. Lacking a unified strategy (or army) and fighting a defensive campaign, from April onwards the army lost cohesion and its special advantages. Successes continued for some time: Thouars was taken in early May and Saumur in June; there were victories at Châtillon and Vihiers. After this string of victories, the Vendeans turned to a protracted siege of Nantes, for which they were unprepared and which stalled their momentum, giving the government in Paris sufficient time to send more troops and experienced generals.

...

Wikipedia