Phosgene attack 19 December 1915

| Phosgene attack 19 December 1915 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of Local operations December 1915 – June 1916 Western Front, World War I | |||||||

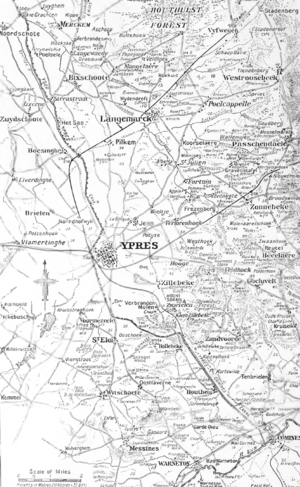

Map of the Ypres district |

|||||||

|

|||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

|

||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

|

||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| Elements of 2 corps specialist Pioneer regiment |

2 divisions | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| unknown | 1,069 (gas only) |

||||||

|

Ypres in West Flanders, Belgium

|

|||||||

The Phosgene attack 19 December 1915 was the first use of phosgene gas by the Germans against British troops, during World War I, at Wieltje north-east of Ypres in Belgian Flanders. German gas attacks on allied troops had begun on 22 April 1915, during the Second Battle of Ypres using chlorine gas, against French and Canadian units. The surprise led to the capture of much of the Ypres Salient, after which the effectiveness of gas as a weapon diminished, as the French and British produced anti-gas helmets. The German Nernst-Duisberg-Commission investigated the feasibility of adding the much more lethal phosgene to chlorine gas. Mixed chlorine and phosgene gas was used at the end of May 1915, in attacks against French troops on the Western Front and on the Eastern Front against the Russian army.

In December 1915, the 4th Army used the mixture of chlorine and phosgene against British troops on the Western Front in Flanders during an attack at Wieltje near Ypres. Before the attack, the British had taken a prisoner who disclosed the plan and had also gleaned information from other sources, which had led to the divisions of VI Corps being alerted from 15 December. The gas discharge on 19 December was accompanied by German raiding parties, most of which were engaged with small-arms fire while attempting to cross no-man's land. British anti-gas precautions prevented a panic or a collapse of the defence, even though British anti-gas helmets had not been treated to repel phosgene. Only the 49th Division had a large number of gas casualties, caused by soldiers in reserve lines not being warned of the gas in time to put on their helmets. A study by British medical authorities, arrived at a figure of 1,069 gas casualties, of whom 120 men died. After the operation, the Germans concluded that a breakthrough could not be achieved solely by the use of gas.

During the evening of 22 April 1915, German pioneers released chlorine gas from cylinders placed in trenches at the Ypres Salient. The gas drifted into the positions of the French 87th Territorial and the 45th Algerian divisions, which occupied the north side of the salient and caused many of the troops to run back from the cloud. A gap had been made in the Allied line, which if exploited by the Germans, could have eliminated the salient and led to the capture of Ypres. The German attack was intended as a strategic diversion, rather than a breakthrough attempt and insufficient forces were available to follow up the success. As soon as German troops tried to advance into areas not affected by the gas, Allied small-arms and artillery fire dominated the area and halted the German advance.

...

Wikipedia