L. Cornelius Sulla

| Lucius Cornelius Sulla | |

|---|---|

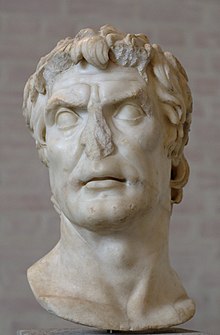

Apparent bust of Sulla in the Munich Glyptothek

|

|

| Dictator of the Roman Republic | |

|

In office 82 or 81 BC – 81 BC |

|

| Preceded by | Gaius Servilius Geminus in 202 BC |

| Succeeded by | Gaius Julius Caesar in 49 BC |

| Consul of the Roman Republic | |

|

In office 88 BC – 88 BC |

|

| Preceded by | Gnaeus Pompeius Strabo and Lucius Porcius Cato |

| Succeeded by | Lucius Cornelius Cinna and Gnaeus Octavius |

| Consul of the Roman Republic | |

|

In office 80 BC – 80 BC |

|

| Preceded by | Gnaeus Cornelius Dolabella and Marcus Tullius Decula |

| Succeeded by | Appius Claudius Pulcher and Publius Servilius Vatia |

| Personal details | |

| Born | c. 138 BC Rome, Roman Republic |

| Died | 78 BC (aged c. 60) Puteoli, Roman Republic |

| Political party | Optimates |

| Spouse(s) | first wife Julia Caesaris, second wife Aelia, third wife Cloelia, fourth wife Caecilia Metella, fifth wife Valeria |

| Children | Lucius Cornelius Sulla, Cornelia, Faustus Cornelius Sulla, Cornelia Fausta, Cornelia Postuma |

Lucius Cornelius Sulla Felix (/ˈsʌlə/; c. 138 BC – 78 BC), known commonly as Sulla, was a Roman general and statesman. He had the distinction of holding the office of consul twice, as well as reviving the dictatorship. Sulla was a skillful general, achieving numerous successes in wars against different opponents, both foreign and Roman. He was awarded a grass crown, the most prestigious Roman military honor, during the Social War.

Sulla's dictatorship came during a high point in the struggle between optimates and populares, the former seeking to maintain the Senate's oligarchy, and the latter espousing populism. In a dispute over the eastern army command (initially awarded to Sulla by the Senate but withdrawn as a result of Gaius Marius's intrigues) Sulla marched on Rome in an unprecedented act and defeated Marius in battle. In 81 BC, after his second march on Rome, he revived the office of dictator which had been inactive since the Second Punic War over a century before, and used his powers to enact a series of reforms to the Roman Constitution, meant to restore the primacy of the Senate and limit tribune power. Sulla's ascension was also marked by political purges in proscriptions. After seeking election to and holding a second consulship, he retired to private life and died shortly after.

Sulla's decision to seize power – ironically enabled by his rival's military reforms that bound the army's loyalty with the general rather than to Rome – permanently destabilized the Roman power structure. Later leaders like Julius Caesar would follow his precedent in attaining political power through force.

...

Wikipedia