John Lind (politician)

| John Lind | |

|---|---|

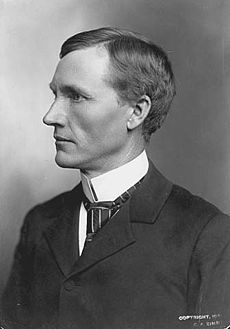

John Lind in 1899

|

|

| Member of the U.S. House of Representatives from Minnesota's 5th district |

|

|

In office March 4, 1903 – March 3, 1905 |

|

| Preceded by | Loren Fletcher |

| Succeeded by | Loren Fletcher |

| 14th Governor of Minnesota | |

|

In office January 2, 1899 – January 7, 1901 |

|

| Lieutenant | Lyndon Ambrose Smith |

| Preceded by | David Marston Clough |

| Succeeded by | Samuel Rinnah Van Sant |

| Member of the U.S. House of Representatives from Minnesota's 2nd district |

|

|

In office March 4, 1887 – March 3, 1893 |

|

| Preceded by | James Wakefield |

| Succeeded by | James McCleary |

| Personal details | |

| Born |

March 25, 1854 Småland Sweden |

| Died | September 18, 1930 (aged 76) Minneapolis, Minnesota, United States |

| Political party | Democratic |

| Spouse(s) | Alice A. Shepard |

| Alma mater | University of Minnesota Law School |

| Profession | educator |

| Religion | Unitarian |

John Lind (March 25, 1854 – September 18, 1930) was an American politician. Lind played an important role in the Mexican Revolution as President Woodrow Wilson's personal envoy.

Lind was born in Kånna, Kronoberg County in the Swedish province of Småland and emigrated to the United States with his parents when he was thirteen years old. He served in the Spanish–American War in 1898. A former teacher and superintendent, he later graduated from the University of Minnesota Law School.

Lind settled in New Ulm to practice law. Most of the inhabitants were German, but Lind adjusted by learning to speak German almost as fluently as he could Swedish. He was soon known among the lawyers across the ninth circuit and so devoted to his practice that in the very convention that first nominated him to Congress, he left before proceedings had closed to attend to a client in the court down at Lincoln County. He joined the Republican party almost as soon as he set up his office; most Swedes made the same choice in Minnesota. While he could not yet vote in the 1872 presidential election, he stood at the polls to hand out ballots. Party loyalty brought the usual rewards: a receivership in the United States Land Office in 1881, and in 1886 a Republican nomination to Congress.

Lind was no great orator, but he had special advantages. The Second Minnesota Congressional District was Republican, generally by a two-to-one margin. The Swedish vote was dependably in favor of Lind, as well, and so were the Germans in New Ulm, thanks to his wide professional acquaintanceship with them. In addition, farmers resented the duty on binding-twine in the protective tariff, and Lind placed himself among the moderate tariff revisionists. At the north end of the state, his support for placing lumber on the duty-free list would have been political suicide. On the southern prairies, it was a far more popular position. Lind had other reasons for his stand. Concerned over the destruction of the nation's forests and a strong supporter for the national timber-culture law, he hoped that a larger importation of foreign lumber would slacken the timber companies' appetite for American trees.

...

Wikipedia