History of the British Raj

Imperial entities of India

|

|

| Dutch India | 1605–1825 |

|---|---|

| Danish India | 1620–1869 |

| French India | 1668–1954 |

|

|

|

| Casa da Índia | 1434–1833 |

| Portuguese East India Company | 1628–1633 |

|

|

|

| East India Company | 1612–1757 |

| Company rule in India | 1757–1858 |

| British Raj | 1858–1947 |

| British rule in Burma | 1824–1948 |

| Princely states | 1721–1949 |

| Partition of India |

1947

|

|

|

|

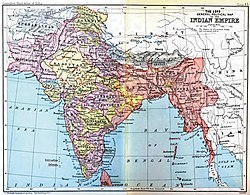

The history of the British Raj refers to the period of British rule on the Indian subcontinent between 1858 and 1947. The system of governance was instituted in 1858 when the rule of the East India Company was transferred to the Crown in the person of Queen Victoria (who in 1876 was proclaimed Empress of India). It lasted until 1947, when the British provinces of India were partitioned into two sovereign dominion states: the Dominion of India and the Dominion of Pakistan, leaving the princely states to choose between them. The two new dominions later became the Republic of India and the Islamic Republic of Pakistan (the eastern half of which, still later, became the People's Republic of Bangladesh). The province of Burma in the eastern region of the Indian Empire had been made a separate colony in 1937 and became independent in 1948.

In the latter half of the 19th century, both the direct administration of India by the British crown and the technological change ushered in by the industrial revolution, had the effect of closely intertwining the economies of India and Great Britain. In fact many of the major changes in transport and communications (that are typically associated with Crown Rule of India) had already begun before the Mutiny. Since Dalhousie had embraced the technological change then rampant in Great Britain, India too saw rapid development of all those technologies. Railways, roads, canals, and bridges were rapidly built in India and telegraph links equally rapidly established in order that raw materials, such as cotton, from India's hinterland could be transported more efficiently to ports, such as Bombay, for subsequent export to England. Likewise, finished goods from England were transported back just as efficiently, for sale in the rising(burgeoning) Indian markets. However, unlike Britain itself, where the market risks for the infrastructure development were borne by private investors, in India, it was the taxpayers—primarily farmers and farm-labourers—who endured the risks, which, in the end, amounted to £50 million. In spite of these costs, very little skilled employment was created for Indians. By 1920, with a history of 60 years of its construction, only ten per cent of the "superior posts" in the railways were held by Indians.

...

Wikipedia