Fomepizole

|

|

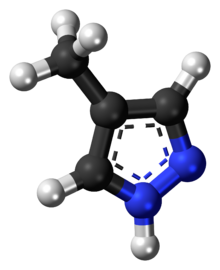

Chemical structure of fomepizole

|

|

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Trade names | Antizol, others |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Monograph |

| Pregnancy category |

|

| Routes of administration |

intravenous |

| ATC code | |

| Identifiers | |

|

|

| Synonyms | 4-Methylpyrazole |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| DrugBank | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| KEGG | |

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.028.587 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

| Formula | C4H6N2 |

| Molar mass | 82.11 g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (Jmol) | |

| Density | 0.99 g/cm3 |

| Boiling point | 204 to 207 °C (399 to 405 °F) (at 97,3 kPa) |

|

|

|

|

Fomepizole, also known as 4-methylpyrazole, is a medication used to treat methanol and ethylene glycol poisoning. It may be used alone or in together with hemodialysis. It is given by injection into a vein.

Common side effects include headache, nausea, sleepiness, and unsteadiness. It is unclear if use during pregnancy is safe for the baby. Fomepizole works by blocking the enzyme that converts methanol and ethylene glycol to their toxic breakdown products.

Fomepizole was approved for medical use in the United States in 1997. It is on the World Health Organization's List of Essential Medicines, the most effective and safe medicines needed in a health system. In the United States each vial costs about 1000 USD.

Fomepizole is used in ethylene glycol and methanol toxic ingestion and acts to inhibit the breakdown of these toxins into their active toxic metabolites. Fomepizole is a competitive inhibitor of the enzyme alcohol dehydrogenase, found in the liver. This enzyme plays a key role in the metabolism of ethylene glycol and methanol.

By competitively inhibiting the first enzyme in the metabolism of ethylene glycol and methanol, fomepizole slows the production of the toxic metabolites. The slower rate of metabolite production allows the liver to process and excrete the metabolites as they are produced, limiting the accumulation in tissues such as the kidney and eye. As a result, much of the organ damage is avoided.

Fomepizole is most effective when given soon after ingestion of ethylene glycol or methanol. Delaying its administration allows for the generation of harmful metabolites.

Concurrent use with ethanol is contraindicated because fomepizole is known to prolong the half-life of ethanol. Extending the half-life of ethanol may increase and extend the intoxicating effects of ethanol, allowing for greater (potentially dangerous) levels of intoxication at lower doses. Fomepizole slows the production of acetaldehyde by inhibiting alcohol dehydrogenase, which in turn allows more time to further convert acetaldehyde into acetic acid (vinegar) by acetaldehyde dehydrogenase. The result is a patient with a prolonged and deeper level of intoxication for any given dose of ethanol, and reduced "hangover" symptoms (since these adverse symptoms are largely mediated by acetaldehyde build up). In a chronic alcoholic who has built up a tolerance to ethanol, this removes some of the disincentives to ethanol consumption ("negative reinforcement") while allowing them to become intoxicated with a lower dose of ethanol. The danger is that the alcoholic will then overdose on ethanol (possibly fatally). If alcoholics instead very carefully reduce their doses to reflect the now slower metabolism, they may get the "rewarding" stimulus of intoxication at lower doses with less adverse "hangover" effects - leading potentially to increased psychological dependency. However, these lower doses may therefore produce less chronic toxicity and provide a harm minimization approach to chronic alcoholism. It is, in essence, the antithesis of a disulfiram approach which tries to increase the buildup of acetaldehyde resulting in positive punishment for the patient (needless to say compliance / adherence is a substantial problem in disulfiram-based approaches). Disulfiram also has a considerably longer half-life than that of fomepizole, requiring the person to not drink ethanol in order to avoid severe effects. If the person is not adequately managed on a benzodiazepine, barbiturate, acamprosate, or another GABAA receptor agonist, the alcohol withdrawal syndrome (known as delerium tremens "DT") may occur; disulfiram treatment should never be initiated until the risk for DT has been evaluated and mitigated appropriately, but fomepazole treatment may be initiated while the DT de-titration sequence is still being calibrated based upon person's withdrawal symptoms and psychological health.

...

Wikipedia