Ferdinand Hurter

| Ferdinand Hurter | |

|---|---|

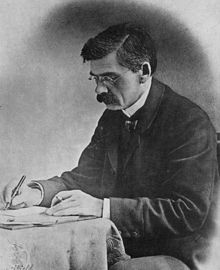

Ferdinand Hurter. Photograph taken by his colleague in photographic research, Vero Charles Driffield

|

|

| Born | 15 March 1844 Schaffhausen, Switzerland |

| Died |

12 March 1898 (aged 53) Cressington Park, Liverpool |

| Residence | England |

| Nationality | Swiss |

| Fields | Chemist |

| Institutions | Gaskell, Deacon & Co., United Alkali Company |

| Alma mater | Zürich Polytechnic, Heidelberg University |

| Doctoral advisor | Robert Bunsen, Gustav Kirchhoff |

| Known for | chemistry, photographic research |

| Notable awards | Progress Medal of the Royal Photographic Society, 1898 |

Ferdinand Hurter (15 March 1844 – 12 March 1898) was a Swiss industrial chemist who settled in England. He also carried out research into photography.

Ferdinand Hurter was born in Schaffhausen, Switzerland, the only son of Tobias Hurter, a bookbinder, and his wife Anna Oechslein. His father died when Ferdinand was aged only two and his mother worked as a nurse to support him and his sister Elizabeth. She later married her late husband's half-brother, David, and Ferdinand developed a strong relationship with his stepfather. After education at the local Gymnasium he became an apprentice to a dyer in Winterthur before moving to Zürich to work in a silk firm. He then attended Zürich Polytechnic before going to Heidelberg University. Here he studied chemistry under Robert Bunsen and physics under Gustav Kirchhoff. He graduated Ph.D. with the highest honours in 1866.

Hurter was offered a professorship in Aarau but declined this and, with a few letters of introduction, arrived in Manchester in 1867. He joined Henry Deacon and Holbrook Gaskell at their alkali manufacturing business, Gaskell, Deacon & Co., in Widnes, Lancashire. Here he became chief chemist and worked with Deacon to develop a process to convert hydrochloric acid, a waste by-product of the Leblanc process of making alkali, to chlorine which was then used to manufacture bleaching powder. He was a pioneer in applying the principles of physical chemistry and thermodynamics to industrial processes and by 1880 was considered to be a world authority on the manufacture of alkali. He was a strong defender of the Leblanc process against the other methods of manufacturing alkali being developed at the time although he did research the ammonia-soda process but without any success. He argued against the production of alkali by the electrolysis of brine because of the enormous amount of electrical power this would require although he was later to have second thoughts.

...

Wikipedia