Eider Canal

| Eider Canal | |

|---|---|

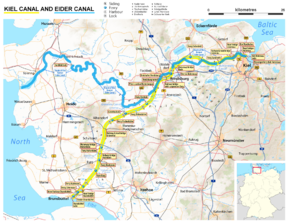

Map of the Eider Canal (blue) and succeeding Kiel Canal in Schleswig-Holstein

|

|

| Specifications | |

| Length | 107 miles (172 km) (Man-made segment ran for 26 miles (42 km)) |

| Locks | 6 |

| Maximum height above sea level | 23 ft (7.0 m) |

| Status | replaced by Kiel Canal |

| History | |

| Date of act | 14 April 1774 |

| Construction began | 1776 |

| Date completed | 1784 |

| Date closed | 1887 |

| Geography | |

| Start point | Tönning (North Sea) |

| End point | Kiel (Baltic Sea) |

The Eider Canal (also called the Schleswig-Holstein Canal) was an artificial waterway in southern Denmark (later northern Germany) which connected the North Sea with the Baltic Sea by way of the rivers Eider and Levensau. Constructed between 1777 and 1784, the Eider Canal was built to create a path for ships entering and exiting the Baltic that was shorter and less storm-prone than navigating around the Jutland peninsula. In the 1880s the canal was replaced by the enlarged Kiel Canal, which includes some of the Eider Canal's watercourse.

The canal's watercourse followed the border between the duchies of Schleswig and Holstein, and from the time of its construction it was known as the "Schleswig-Holstein Canal". After the First Schleswig War, the Danish government renamed the waterway the "Eider Canal" to resist the German nationalist idea of Schleswig-Holstein as a single political entity; but, when the region passed into Prussian control after the Second Schleswig War, the name was reverted to the "Schleswig-Holstein Canal." In modern historiography the canal is referred to by either name.

As early as 1571 Duke Adolf I of Holstein-Gottorp proposed to build an artificial waterway across Schleswig-Holstein by connecting an eastward bend of the River Eider to the Baltic Sea, so as to compete with the nearby Stecknitz Canal for merchant traffic. At the time the Duke of Holstein-Gottorp was a vassal of the Kingdom of Denmark, but the dukes of Schleswig-Holstein were perennial enemies to their Danish suzerains, and the political fragmentation of the region and the ongoing conflict over its rightful rule posed an insurmountable obstacle to such a large project. The prospect of a canal was again raised in the 1600s under King Christian IV and Duke Frederick III.

...

Wikipedia