Antineutron

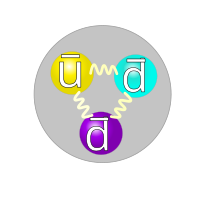

The quark structure of the antineutron.

|

|

| Classification | Antibaryon |

|---|---|

| Composition | 1 up antiquark, 2 down antiquarks |

| Statistics | Fermionic |

| Interactions | Strong, Weak, Gravity, Electromagnetic |

| Status | Discovered |

| Symbol | n |

| Particle | Neutron |

| Discovered | Bruce Cork (1956) |

| Mass | 939.565560(81) MeV/c2 |

| Electric charge | 0 |

| Magnetic moment | +1.91 µN |

| Spin | 1⁄2 |

| Isospin | 1⁄2 |

The antineutron is the antiparticle of the neutron with symbol

n

. It differs from the neutron only in that some of its properties have equal magnitude but opposite sign. It has the same mass as the neutron, and no net electric charge, but has opposite baryon number (+1 for neutron, −1 for the antineutron). This is because the antineutron is composed of antiquarks, while neutrons are composed of quarks. The antineutron consists of one up antiquark and two down antiquarks.

Since the antineutron is electrically neutral, it cannot easily be observed directly. Instead, the products of its annihilation with ordinary matter are observed. In theory, a free antineutron should decay into an antiproton, a positron and a neutrino in a process analogous to the beta decay of free neutrons. There are theoretical proposals that neutron–antineutron oscillations exist, a process which would occur only if there is an undiscovered physical process that violates baryon number conservation.

The antineutron was discovered in proton–antiproton collisions at the Bevatron (Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory) by Bruce Cork in 1956, one year after the antiproton was discovered.

...

Wikipedia