Ye Mingchen

| Ye Mingchen | |

|---|---|

|

|

| Governor of Liangguang | |

|

In office 1852–1858 |

|

| Preceded by | Xu Guangjin |

| Succeeded by | Huang Zonghan |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 21 December 1807 Hanyang, Hubei |

| Died | April 9, 1859 (aged 51) Calcutta, India |

| Resting place | Hanyang |

| Occupation | Politician, Imperial viceroy |

| Ye Mingchen | |||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 葉名琛 | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Simplified Chinese | 叶名琛 | ||||||||

|

|||||||||

| Transcriptions | |

|---|---|

| Standard Mandarin | |

| Hanyu Pinyin | Yè Míngchēn |

| Wade–Giles | Yeh Ming-ch'en |

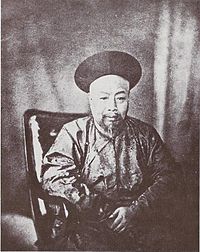

Ye Mingchen (葉名琛, 1807–1859), also romanized as Yeh Ming-ch'en, was a high-ranking Chinese official during the Qing dynasty, known for his resistance to British influence in Canton (now known as Guangzhou) in the aftermath of the First Opium War and his role in the beginning of the Second Opium War.

Ye came from a scholarly family in Hubei province, son of Ye Zhishen 葉志詵 and a connoisseur of antiquities. He was awarded the juren 舉人 degree in 1837, the jinshi 進士, or highest degree, in 1835, after which he briefly held the position of compiler in the imperial elite school, the Hanlin Academy 翰林院. In 1838, Ye received his first official appointment as prefect of Xing'an in Shaanxi province and he subsequently rose rapidly through the ranks in the Qing civil service. In the following years he served as circuit intendant of Yanping in Shanxi province, salt inspector in Jiangxi, surveillance commissioner in Yunnan and financial commissioner first in Hunan, later in Gansu and finally Guangdong province, of which he became governor in 1848, just as the Taiping Rebellion was breaking out.

Around 1850, Ye Mingchen and his father established an association in the western suburbs of Guangzhou to worship Lü Dongbin, one of the Daoist Eight Immortals known for helping the common people, and to provide medical prescriptions. Ye is said to have commanded troops in battle on the basis of communications with Lü. Some unsympathetic observers account for his inadequate preparations, misplaced confidence, and the ease with which the British captured him by pointing to his belief in occult Daoism and oracular divination.

...

Wikipedia