Winnebago War

| Winnebago War | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the American Indian Wars | |||||||||

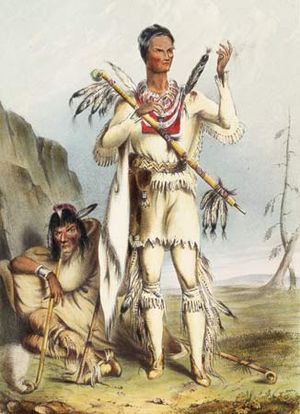

Red Bird, dressed in white buckskin for his surrender to U.S. authorities, with Wekau |

|||||||||

|

|||||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||||

| Prairie La Crosse Ho-Chunks, with a few allies |

|

||||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||||

| Red Bird |

Henry Atkinson, Henry Dodge |

||||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||||

| 7 killed | 9–11 civilians killed | ||||||||

The Winnebago War, also known as the Winnebago Uprising, was a brief conflict that took place in 1827 in the Upper Mississippi River region of the United States, primarily in what is now the state of Wisconsin. Not quite a war, the hostilities were limited to a few attacks on American civilians by a portion of the Winnebago (or Ho-Chunk) Native American tribe. The Ho-Chunks were reacting to a wave of lead miners trespassing on their lands, and to false rumors that the United States had sent two Ho-Chunk prisoners to a rival tribe for execution.

Most Native Americans in the region decided against joining the uprising, and so the conflict ended after U.S. officials responded with a show of military force. Ho-Chunk chiefs surrendered eight men who had participated in the violence, including Red Bird, who American officials believed to be the ringleader. Red Bird died in prison in 1828 while awaiting trial; two other men convicted of murder were pardoned by President John Quincy Adams and released.

As a result of the war, the Ho-Chunk tribe was compelled to cede the lead mining region to the United States. The Americans also increased their military presence on the frontier, building Fort Winnebago and reoccupying two other abandoned forts. The conflict convinced some officials that Americans and Indians could not live peaceably together, and that the Natives should be compelled to move westward, a policy known as Indian removal. The Winnebago War preceded the larger Black Hawk War of 1832, which involved many of the same people and concerned similar issues.

Following the War of 1812, the United States pursued a policy of trying to prevent wars among Native Americans in the Upper Mississippi River region. This was not strictly for humanitarian reasons: intertribal warfare made it more difficult for the United States to acquire Indian land and move the tribes to the West, a policy known as Indian removal, which had become the primary goal by the late 1820s. On August 19, 1825, U.S. officials finalized a multi-tribal treaty at Prairie du Chien, which defined the boundaries of the region's tribes.

...

Wikipedia