Taos Revolt

| Taos Revolt | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Mexican–American War | |||||||

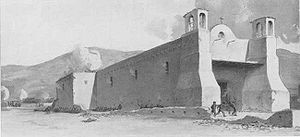

The Siege of Taos, depicting John Burgwin's death. (far right) |

|||||||

|

|||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

|

||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

Sterling Price John Burgwin† Ceran St. Vrain Israel R. Hendley† Jesse I. Morin |

Pablo Chavez† Pablo Montoya† Jesus Tafoya† Tomás ("Tomasito") Romero† Manuel Cortez |

||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| 19 killed ~70 wounded |

~100 killed ~250 wounded ~400 captured |

||||||

| Civilian Casualties: ~20 killed | |||||||

The Taos Revolt was a popular insurrection in January 1847 by Mexicans and Pueblo allies against the United States' occupation of present-day northern New Mexico during the Mexican–American War. In two short campaigns, United States troops and militia crushed the rebellion of the Mexicans and their allies. The rebels regrouped and fought three more engagements, but after being defeated, they abandoned open warfare.

In August 1846, the territory of New Mexico, then under Mexican rule, fell to U.S. forces under Stephen Watts Kearny. Governor Manuel Armijo surrendered at the Battle of Santa Fe without firing a shot. When Kearny departed with his forces for California, he left Colonel Sterling Price in command of U.S. forces in New Mexico. He appointed Charles Bent as New Mexico's first territorial governor.

Many New Mexicans were unreconciled to Armijo's surrender; they also resented their treatment by U.S. soldiers, which Governor Bent described:

"As other occupation troops have done at other times and places have done, they undertook to act like conquerors." Gov. Bent implored Price's superior, Col. Alexander Doniphan, "to interpose your authority to compel the soldiers to respect the rights of the inhabitants. These outrages are becoming so frequent that I apprehend serious consequences must result sooner or later if measures are not taken to prevent them."

An issue more significant than the galling daily insults was that many New Mexican citizens feared that their land titles, issued by the Mexican government, would not be recognized by the United States. They worried that American sympathizers would prosper at their expense. Following Kearny's departure, dissenters in Santa Fe plotted a Christmas uprising. When the plans were discovered by the US authorities, the dissenters postponed the uprising. They attracted numerous Native American allies, including Puebloan peoples, who also wanted to push the Americans from the territory.

...

Wikipedia