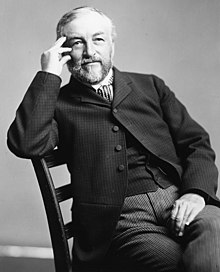

Samuel Langley

| Samuel Pierpont Langley | |

|---|---|

Samuel Pierpont Langley

|

|

| Born |

August 22, 1834 Roxbury, Massachusetts |

| Died | February 27, 1906 (aged 71) Aiken, South Carolina |

| Nationality | United States |

| Fields |

Astronomy Aviation |

| Known for | Solar physics |

| Notable awards |

Rumford Medal (1886) Henry Draper Medal (1886) Janssen Medal (1893) |

Samuel Pierpont Langley (/ˈlæŋli/; August 22, 1834 – February 27, 1906) was an American astronomer, physicist, inventor of the bolometer and pioneer of aviation. He attended Boston Latin School, graduated from English High School of Boston, was an assistant in the Harvard College Observatory, then moved to a job ostensibly as a professor of mathematics at the United States Naval Academy, but actually was sent there to restore the Academy's small observatory. In 1867, he became the director of the Allegheny Observatory and a professor of astronomy at the Western University of Pennsylvania, now known as the University of Pittsburgh, a post he kept until 1891 even while he became the third Secretary of the Smithsonian Institution in 1887. Langley was the founder of the Smithsonian Astrophysical Observatory.

Langley arrived in Pittsburgh in 1867 to become the first director of the Allegheny Observatory, after the institution had fallen into hard times and been given to the Western University of Pennsylvania. By then, the department was in disarray – equipment was broken, there was no library and the building needed repairs. Through the friendship and aid of William Thaw, a Pittsburgh industrial leader, Langley was able to improve the observatory equipment and build additional apparatuses. One of the new instruments was a small transit telescope used to observe the position of the stars as they cross the celestial meridian. He raised money for the department in large part by distributing standard time to cities and railroads. Up until then, correct time had only occasionally been sent from American observatories for public use. Clocks were manually wound in those days and time tended to be imprecise. Exact time had not been especially necessary. It was enough to know that at noon the sun was directly above the head. All that until railroad tracks were installed.

...

Wikipedia