Robert Rawlinson

| Robert Rawlinson | |

|---|---|

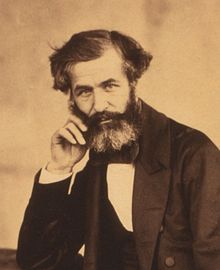

Robert Rawlinson in Crimea, 1855

|

|

| Born | 28 February 1810 Bristol, England |

| Died | 31 May 1898 (aged 88) London, England |

| Nationality | English |

| Engineering career | |

| Discipline | Civil, |

| Institutions | Institution of Civil Engineers (president), |

Sir Robert Rawlinson KCB (28 February 1810 – 31 May 1898) was an English engineer and sanitarian.

He was born at Bristol. His father was a mason and builder at Chorley, Lancashire, and he himself began his engineering education by working in a stonemason's yard.

In 1831, he obtained employment under Jesse Hartley in the engineers office at the Liverpool docks, and for four years from 1836 he was engaged under Robert Stephenson as assistant resident engineer for the Blisworth section of what is now the London & North-Western main line from London to the North.

Returning to Liverpool, he spent some years as assistant-surveyor to the corporation, and then in 1844 accepted an engineering post on the Bridgewater Canal. Three years later he returned to Liverpool, to superintend the design and construction of the famous brick-arched ceiling in the St George's Hall, in succession to, his friend H. L. Elmes. During this period Rawlinson's reputation as a sanitarian had been growing. In 1847 he devised a scheme to supply from Bala Lake in Gwynedd, Wales to Liverpool. When the Public Health Act was passed in 1848 he was appointed one of the first inspectors under it. He inspected many of the chief towns of England, and his reports on the sanitary conditions he found brought him in many cases into great unpopularity with the municipal rulers.

Early in 1855 popular feeling was so aroused by the waste of life that was going on among the British troops in the Crimea through disease, and by the mismanagement of the campaign, that the Aberdeen ministry was forced to resign. Lord Palmerston, who then became prime minister, sent a sanitary commission, consisting of Rawlinson and two medical members (Dr. John Sutherland and Dr. Hector Gavin), with full powers from the War Office, to do whatever it thought would lead to better hygienic conditions in camp and hospital. The commission reached Constantinople in March, and, by insisting on what now seem the most obvious precautions, succeeded within a few weeks in reducing the death-rate in the Levantine hospitals from 42 to 2¼%. Passing on to the Crimea, it effected a similar improvement there, and by the end of the year the health of the whole British army in the field was even better than it enjoyed at home.

...

Wikipedia