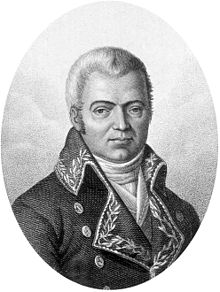

Pierre Marie Auguste Broussonet

| Pierre Marie Auguste Broussonet | |

|---|---|

Pierre Marie Auguste Broussonet

|

|

| Born |

28 February 1761 Montpellier, France |

| Died | 17 January 1807 (aged 45) Montpellier, France |

| Nationality | French |

| Fields | |

| Institutions |

Royal Society National Assembly of France |

| Alma mater | Université de Montpellier |

| Author abbrev. (botany) | Brouss. |

| Spouse | Gabrielle Mitteau |

| Children |

|

Pierre Marie Auguste Broussonet (28 February 1761 – 17 January 1807), French naturalist, was born at Montpellier. His father, François Broussonet (1722-1792), was a physician and professor of medicine at famous Université de Montpellier. His brother, Victor, studied there and later became its dean. Henri Fouquet (1727-1806), a professor at the medical school, was a relative, as was Jean-Antoine Chaptal (1756-1832), who subsequently became minister of the interior.

As a child, Pierre showed a passion for natural history, cluttering his father’s house with specimen collections. In school, he excelled in classical studies in Montpellier, Montélimar, and Toulouse. Because of family tradition, he was headed toward studying medicine, which, at that time, included the study of the natural sciences which had not yet split off to form a separate discipline. Antoine Gouan (1733-1821), a convinced Linnaean, taught at the Montpellier medical school - apparently it was from him that Broussonet learned of Linnaeus’ work. His thesis was entitled Mémoire pour servir à l'histoire de la respiration des poissons, which he defended in 1778. He received his doctorate on 27 May 1779, at the age of eighteen.

Broussonet’s thesis was unanimously praised. Despite his youth, the professors of the University of Montpellier asked that he be made his father’s successor when the latter retired (a rare but not uncommon request). The request was not granted, in spite of Broussonet himself traveling to Paris to plead his cause. But while in Paris he established friendships scholars who made it possible for him to continue his studies on fish. Although the Paris ichthyological collections surpassed those that Broussonet had worked from in the South, they were not comprehensive enough for the classification work he wished to pursue. Ultimately, he went to England to seek the specimens needed for the morphological and systematic work he had in mind.

1780 London offered Broussonet all he could wish for: an active scientific community; naturalists already embracing Linnaeus’ ideas; collections rich in new species; and an influential friend, Sir Joseph Banks (1743-1820). With his promotion, Broussonet was elected to the Royal Society.

...

Wikipedia