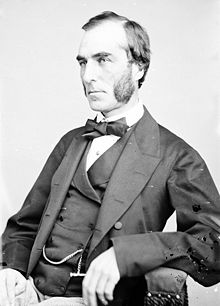

Goldwin Smith

| Goldwin Smith | |

|---|---|

|

|

| Born |

13 August 1823 Reading, England |

| Died | 7 June 1910 (aged 86) The Grange, Toronto, Ontario, Canada |

| Resting place | St James's Cemetery |

| Nationality | British |

| Education | Eton College |

| Alma mater | Magdalen College, Oxford |

| Occupation | Historian |

| Title | Regius Professor of Modern History |

| Term | 1858–1866 |

| Predecessor | Henry Halford Vaughan |

| Successor | William Stubbs |

| Parent(s) | Richard Pritchard Smith, Elizabeth Breton |

| Signature | |

Goldwin Smith (13 August 1823 – 7 June 1910) was a British historian and journalist, active in the United Kingdom and Canada.

Smith was born at Reading, Berkshire. He was educated at Eton College and Magdalen College, Oxford, and after a brilliant undergraduate career he was elected to a fellowship at University College, Oxford. He threw his energy into the cause of university reform with another fellow of University College, Arthur Penrhyn Stanley. On the Royal Commission of 1850 to inquire into the reform of the university, of which Stanley was secretary, Smith served as assistant-secretary; and he was then secretary to the commissioners appointed by the act of 1854. His position as an authority on educational reform was further recognised by a seat on the Popular Education Commission of 1858. In 1868, when the question of reform at Oxford was again growing acute, he published a pamphlet, entitled The Reorganization of the University of Oxford.

In 1865, he led the University of Oxford opposition to a proposal to develop Cripley Meadow north of Oxford railway station for use as a major site of Great Western Railway (GWR) workshops. His father had been a director of GWR. Instead the workshops were located in Swindon. He was public with his pro-Northern sympathies during the American Civil War, notably in a speech at the Free Trade Hall, Manchester in April 1863 and his Letter to a Whig Member of the Southern Independence Association the following year.

Besides the abolition of (religious) tests, effected by the act of 1871, many of the reforms suggested, such as the revival of the faculties, the reorganisation of the professoriate, the abolition of celibacy as a condition of the tenure of fellowships, and the combination of the colleges for lecturing purposes, were incorporated in the act of 1877, or subsequently adopted by the university. Smith gave the counsel of perfection that "pass" examinations ought to cease; but he recognised that this change "must wait on the reorganization of the educational institutions immediately below the university, at which a passman ought to finish his career." His aspiration that colonists and Americans should be attracted to Oxford was later realised by the will of Cecil Rhodes. On what is perhaps the vital problem of modern education, the question of ancient versus modern languages, he pronounced that the latter "are indispensable accomplishments, but they do not form a high mental training" – an opinion entitled to peculiar respect as coming from a president of the Modern Language Association.

...

Wikipedia