Frederich Nietzsche

| Friedrich Nietzsche | |

|---|---|

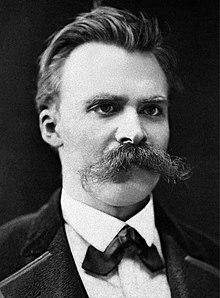

Nietzsche in Basel, c. 1875

|

|

| Born |

Friedrich Wilhelm Nietzsche 15 October 1844 Röcken, Saxony, Prussia |

| Died | 25 August 1900 (aged 55) Weimar, Saxe-Weimar-Eisenach, German Empire |

| Nationality | German |

| Alma mater | |

| Era | 19th-century philosophy |

| Region | Western philosophy |

| School | |

| Institutions | University of Basel |

|

Main interests

|

|

|

Notable ideas

|

|

| Signature | |

Friedrich Wilhelm Nietzsche (/ˈniːtʃə/German: [ˈfʁiːdʁɪç ˈvɪlhɛlm ˈniːtʃə]; 15 October 1844 – 25 August 1900) was a German philosopher, cultural critic, poet, philologist, and Latin and Greek scholar whose work has exerted a profound influence on Western philosophy and modern intellectual history. He began his career as a classical philologist before turning to philosophy. He became the youngest ever to hold the Chair of Classical Philology at the University of Basel in 1869, at the age of 24.

Nietzsche resigned in 1879 due to health problems that plagued him most of his life, and he completed much of his core writing in the following decade. In 1889, at age 44, he suffered a collapse and a complete loss of his mental faculties. He lived his remaining years in the care of his mother until her death in 1897, and then with his sister Elisabeth Förster-Nietzsche, and died in 1900.

Nietzsche's body of work touched widely on art, philology, history, religion, tragedy, culture, and science, and drew early inspiration from figures such as Schopenhauer, Wagner, and Goethe. His writing spans philosophical polemics, poetry, cultural criticism, and fiction while displaying a fondness for aphorism and irony. Some prominent elements of his philosophy include his radical critique of truth in favor of perspectivism; his genealogical critique of religion and Christian morality, and his related theory of master–slave morality; his aesthetic affirmation of existence in response to the "death of God" and the profound crisis of nihilism; his notion of the Apollonian and Dionysian; and his characterization of the human subject as the expression of competing wills, collectively understood as the will to power. In his later work, he developed influential concepts such as the Übermensch and the doctrine of eternal return, and became increasingly preoccupied with the creative powers of the individual to overcome social, cultural, and moral contexts in pursuit of new values and aesthetic health.

...

Wikipedia