Canudos

| Canudos | |

|---|---|

| Municipality | |

] ]

Canudos, circa 1895]

|

|

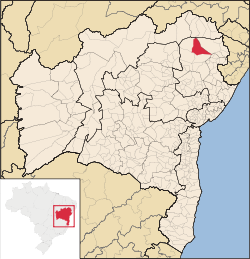

Location in Bahia |

|

| Country |

|

| Region | Nordeste |

| State | Bahia |

| Time zone | UTC -3 |

Canudos is a municipality in the northeast region of Bahia, Brazil. The original town, since flooded by the Cocorobó Dam, was the scene of violent clashes between peasants and republican police in the 1890s.

The municipality contains part of the Raso da Catarina ecoregion.

The town of Canudos was founded in the racially diverseBahia state of northeastern Brazil in 1893 by Antônio Vicente Mendes Maciel, an itinerant preacher from Ceara. Mendes Maciel had been wandering through the backroads and lesser-inhabited areas of the country from the 1870s onwards, followed by a band of loyal supporters. As his following swelled, he took on the name Antônio Conselheiro (Antônio the Counselor) and increasingly began to trouble the local authorities, who saw him as a Monarchist and thus a threat to their legitimacy.

In 1893, following a protest over taxation and a violent melee with the police forces in Masseté, Conselheiro and his band settled on an abandoned farm called Canudos, so called because a plant, canudo-de-pita (scientific name Ipomoea carnea, its popular name referring to its hollow tubes, used for manufacturing smoking pipes) was common in the region. The place was named Belo Monte (Beautiful Mount) by Antonio Conselheiro, but the old name, Arraial de Canudos, prevailed. Over the years people from across Bahia, including landless farmers, former slaves, indigenous people and cangaceiros flocked to join him, and within a few years the fledgling settlement numbered 30,000 people (which made it the second largest urban center in Bahia behind Salvador) and had developed a leather exporting business.

As a community, Canudos operated somewhat like a religious commune, with Antônio Conselheiro as the principal member and director. Canudos was a heavily religious settlement, under the sway of Antonio's fanaticism, but despite his fanaticism he did not assume any official position of authority. Canudos was not explicitly communist, and in fact could even be called monarchistic, but the settlement worked along somewhat communistic lines, practicing common ownership, abolishing the official currency, negating Brazilian national laws, as well as participating collectively in the management of the town. Canudos was in essence a reaction against the contemporary Brazilian nation-state.

...

Wikipedia