Bojangles Robinson

| Bill Robinson | |

|---|---|

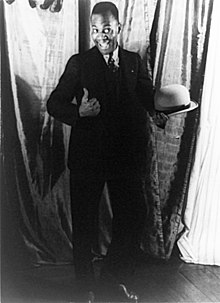

Robinson in 1933

|

|

| Born |

Luther Robinson May 25, 1878 Richmond, Virginia, U.S. |

| Died | November 25, 1949 (aged 71) New York City, New York, U.S. |

| Cause of death | Heart failure |

| Occupation | Dancer, actor, activist |

| Years active | 1900–1943 |

| Spouse(s) | Lena Chase (m.1907–1922; divorced) Fannie S. Clay (m.1922–1943; divorced) Elaine Plaines (m.1944–1949; his death) |

Bill "Bojangles" Robinson (May 25, 1878 – November 25, 1949) was an American tap dancer and actor, the best known and most highly paid African-American entertainer in the first half of the twentieth century. His long career mirrored changes in American entertainment tastes and technology. He started in the age of minstrel shows and moved to vaudeville, Broadway, the recording industry, Hollywood, radio, and television. According to dance critic Marshall Stearns, "Robinson's contribution to tap dance is exact and specific. He brought it up on its toes, dancing upright and swinging", giving tap a "…hitherto-unknown lightness and presence." His signature routine was the stair dance, in which Robinson would tap up and down a set of stairs in a rhythmically complex sequence of steps, a routine that he unsuccessfully attempted to patent. Robinson is also credited with having introduced a new word, copacetic, into popular culture, via his repeated use of it in vaudeville and radio appearances.

A popular figure in both the black and white entertainment worlds of his era, he is best known today for his dancing with Shirley Temple in a series of films during the 1930s, and for starring in the musical Stormy Weather (1943), loosely based on Robinson's own life, and selected for preservation in the National Film Registry. Robinson used his popularity to challenge and overcome numerous racial barriers, including becoming the following:

During his lifetime and afterwards, Robinson also came under heavy criticism for his participation in and tacit acceptance of racial stereotypes of the era, with critics calling him an Uncle Tom figure. Robinson resented such criticism, and his biographers suggested that critics were at best incomplete in making such a characterization, especially given his efforts to overcome the racial prejudice of his era. In his public life Robinson led efforts to:

Despite being the highest-paid black performer of the era, Robinson died penniless in 1949, and his funeral was paid for by longtime friend Ed Sullivan. Robinson is remembered for the support he gave to fellow performers, including Fred Astaire, Lena Horne, Jesse Owens, and the Nicholas brothers.

...

Wikipedia