Uncle Tom

| Uncle Tom | |

|---|---|

| Uncle Tom's Cabin character | |

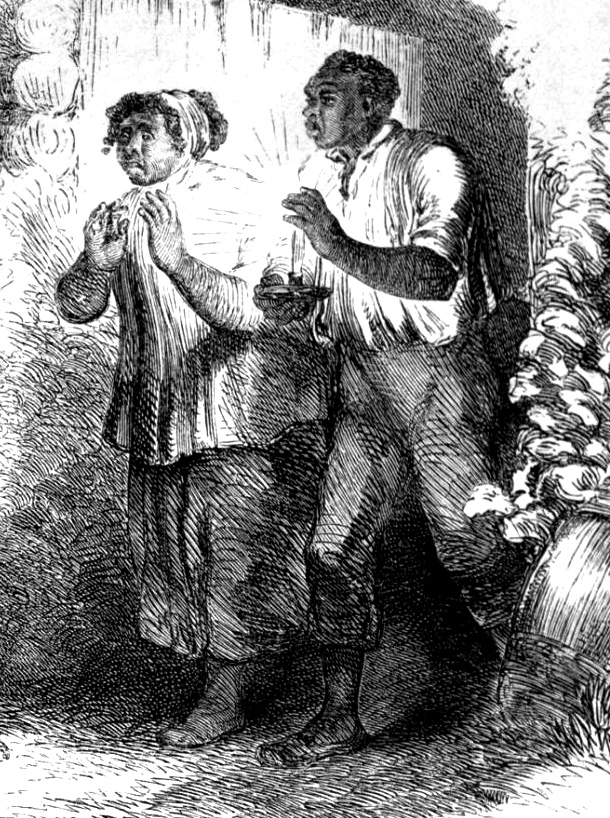

Detail of an illustration from the first book edition of Uncle Tom's Cabin, depicting Uncle Tom as young and muscular.

|

|

| First appearance | Uncle Tom's Cabin |

| Last appearance | Uncle Tom's Cabin |

| Created by | Harriet Beecher Stowe |

| Information | |

| Gender | Male |

| Nationality | American |

Uncle Tom is the title character of Harriet Beecher Stowe's 1852 novel, Uncle Tom's Cabin. The term "Uncle Tom" is also used as a derogatory epithet for an excessively subservient person, particularly when that person is aware of their own lower-class status based on race. The use of the epithet is the result of later works derived from the original novel.

At the time of the novel's initial publication in 1851, Uncle Tom was a rejection of the existing stereotypes of minstrel shows; Stowe's melodramatic story humanized the suffering of slavery for white audiences by portraying Tom as a Jesus-Christ-like figure who is ultimately martyred, beaten to death by a cruel master because he refuses to betray the whereabouts of two women who had escaped from slavery. Stowe reversed the gender conventions of slave narratives by juxtaposing Uncle Tom's passivity against the daring of three African American women who escape from slavery.

The novel was both influential and commercially successful, published as a serial from 1851 to 1852 and as a book from 1852 onward. An estimated 500,000 copies had sold worldwide by 1853, including unauthorized reprints. Senator Charles Sumner credited Uncle Tom's Cabin for the election of Abraham Lincoln and Lincoln himself reportedly quipped that Stowe had triggered the American Civil War.Frederick Douglass praised the novel as "a flash to light a million camp fires in front of the embattled hosts of slavery". Despite Douglass's enthusiasm, an anonymous 1852 reviewer for William Lloyd Garrison's publication The Liberator suspected a racial double standard in the idealization of Uncle Tom:

Uncle Tom's character is sketched with great power and rare religious perception. It triumphantly exemplifies the nature, tendency, and results of Christian non-resistance. We are curious to know whether Mrs. Stowe is a believer in the duty of non-resistance for the White man, under all possible outrage and peril, as for the Black man… [For whites in parallel circumstances, it is often said] Talk not of overcoming evil with good—it is madness! Talk not of peacefully submitting to chains and stripes—it is base servility! Talk not of servants being obedient to their masters—let the blood of tyrants flow! How is this to be explained or reconciled? Is there one law of submission and non-resistance for the Black man, and another of rebellion and conflict for the white man? When it is the whites who are trodden in the dust, does Christ justify them in taking up arms to vindicate their rights? And when it is the blacks who are thus treated, does Christ require them to be patient, harmless, long-suffering, and forgiving? Are there two Christs?

...

Wikipedia