Battle of Đồng Đăng (1885)

| Battle of Đồng Đăng | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Sino-French War, Tonkin Campaign | |||||||

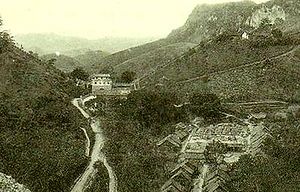

The Gate of China, near Đồng Đăng |

|||||||

|

|||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

|

||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

|

||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 2,000 men | 6,000 men | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| 9 dead 46 wounded |

Unknown | ||||||

The Battle of Đồng Đăng (23 February 1885) was an important French victory during the Sino-French War. It is named after the town of Đồng Đăng, then in northern Tonkin, close to the border between China and Vietnam.

The battle was fought as a pendant to the Lạng Sơn Campaign (3 to 13 February 1885), in which the French captured the Guangxi Army's base at Lạng Sơn.

On 16 February General Louis Brière de l'Isle, the commander of the Tonkin Expeditionary Corps, left Lạng Sơn with Giovanninelli's 1st Brigade to relieve the Siege of Tuyên Quang. Before his departure, he ordered General Oscar de Négrier, who would remain at Lạng Sơn with the 2nd Brigade, to press on towards the Chinese border and expel the battered remnants of the Guangxi Army from Tonkinese soil. After resupplying the 2nd Brigade with food and ammunition, De Négrier advanced to attack the Guangxi Army at Đồng Đăng.

De Négrier's 2nd Brigade numbered just under 2,900 men in February 1885. The brigade's order of battle was as follows:

De Négrier advanced on Đồng Đăng with Herbinger's three line battalions, the two Foreign Legion battalions, a company of Tonkinese riflemen and Roperh and de Saxcé's batteries. Servière's 2nd African Battalion was left to guard Lạng Sơn and the brigade's supply line back to Chu. Martin's battery also remained at Lạng Sơn.

The Chinese had established an extremely strong position, centred on a 300-metre high limestone plateau which rose just to the west of the Mandarin Road and ran due north from Đồng Đăng to the Gate of China and beyond into China itself. This massif overlooked Đồng Đăng and the approaches to the Gate of China, and presented a sheer cliff face towards the southeast. It could only be climbed on its western side, and the Chinese had established a sheltered artillery position on its summit, just behind Đồng Đăng, commanding the steep western slopes that an attacker would have to scale. A number of infantry camps and several other artillery emplacements had been built on the summit.

The left of the Chinese position lay along the hills directly to the east of the Mandarin Road, which were covered by the elevated infantry and artillery positions on the limestone massif. These positions were quite secure against a frontal attack as long as the massif itself remained in Chinese hands. To reach a position from which they could assault the limestone massif the French would first have to take Đồng Đăng, which lay directly in their way. The Chinese had deployed their right wing in and around Đồng Đăng. The small low-lying town was the weakest point in the Chinese position, but the Chinese had done what they could to strengthen it by building three strong forts on the hills to its west, overlooking the villages of Dong Tien and Pho Bu and the That Ke valley. These strongpoints, the ‘Western Forts’, were linked by a defensive line which contained Đồng Đăng itself. The Chinese could also rely on the Đồng Đăng stream, a fast-flowing arroyo which ran across the entire front of their line, to act as a moat for their defences and slow down any French attack.

...

Wikipedia