Abraham Lincoln and slavery

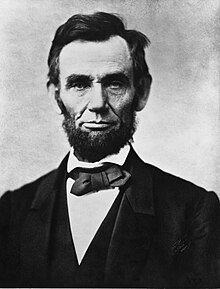

| Abraham Lincoln | |

|---|---|

|

|

| 16th President of the United States | |

|

In office March 4, 1861 – April 15, 1865 |

|

| Vice President |

Hannibal Hamlin Andrew Johnson |

| Preceded by | James Buchanan |

| Succeeded by | Andrew Johnson |

| Personal details | |

| Born |

February 12, 1809 Hodgenville, Kentucky, U.S. |

| Died | April 15, 1865 (aged 56) Washington, D.C., U.S. |

| Political party |

Republican (1854–1865) National Union (1864–1865) |

| Other political affiliations |

Whig (before 1854) |

Abraham Lincoln's position on slavery is one of the central issues in American history.

Lincoln often expressed moral opposition to slavery in public and private. Initially, he expected to bring about the eventual extinction of slavery by stopping its further expansion into any U.S. territory, and by proposing compensated emancipation (an offer Congress applied to Washington, D.C.) in his early presidency. Lincoln stood by the Republican Party's platform of 1860, which stated that slavery should not be allowed to expand into any more territories. He believed that the extension of slavery in new western lands would block "free labor on free soil", and he also wanted a peaceful, enduring end to slavery. As early as the 1850s, Lincoln was politically attacked as an abolitionist, but he did not consider himself one. Howard Jones says that "[i]n the prewar period, as well as into the first months of the American Civil War itself....Lincoln believed it prudent to administer a slow death to slavery through gradual emancipation and voluntary colonization rather than to follow the abolitionist and demanding an immediate end to slavery without compensation to owners." In 1863, Lincoln ordered the freedom of all slaves in the areas "in rebellion" and insisted on enforcement freeing millions of slaves, but he did not call for the immediate end of slavery everywhere in the U.S. until the proposed 13th Amendment became part of his party platform for the 1864 election.

In 1842, Abraham Lincoln married Mary Todd, who was a daughter of a slave-owning family from Kentucky. Lincoln returned to the political stage as a result of the 1854 Kansas–Nebraska Act and soon became a leading opponent of the "Slaveocracy"—that is the political power of the southern slave owners. The Kansas–Nebraska Act, written to form the territories of Kansas and Nebraska, included language, designed by Stephen A. Douglas, which allowed the settlers to decide whether they would or would not accept slavery in their region. Lincoln saw this as a repeal of the 1820 Missouri Compromise which had outlawed slavery above the 36-30' parallel.

...

Wikipedia