1913 lockout

| The Dublin lock-out | |||

|---|---|---|---|

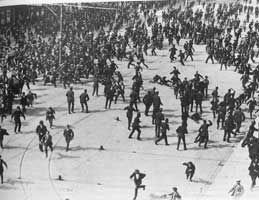

Dublin Metropolitan Police break up a union rally

|

|||

| Date | 26 August 1913 - 18 January 1914 |

||

| Location | Dublin, Ireland | ||

| Caused by |

|

||

| Goals |

|

||

| Methods | Strikes, rallies, walkouts | ||

| Resulted in |

|

||

| Parties to the civil conflict | |||

|

|||

| Lead figures | |||

|

|

|||

| Number | |||

|

|||

| Casualties | |||

|

|||

| 2 dead, several hundred injured | |||

Workers Organizations

Supported by

Employers & Companies

Supported by

The Dublin lock-out was a major industrial dispute between approximately 20,000 workers and 300 employers which took place in Ireland's capital city of Dublin. The dispute lasted from 26 August 1913 to 18 January 1914, and is often viewed as the most severe and significant industrial dispute in Irish history. Central to the dispute was the workers' right to unionise.

Irish workers lived in terrible conditions in tenements. For example, an astonishing 835 people lived in 15 houses in Henrietta Street's Georgian tenements. At number 10, Henrietta Street, the Irish Sisters of Charity ran a laundry inhabited by more than 50 single women. An estimated four million pledges were taken in pawnbrokers every year. The infant mortality rate among the poor was 142 per 1,000 births, extraordinarily high for a European city. The situation was made considerably worse by the high rate of disease in the slums, which was the result of a lack of health care and cramped living conditions, among other things. The most prevalent disease in the Dublin slums at this time was tuberculosis (TB), which spread through tenements very quickly and caused many deaths amongst the poor. A report, published in 1912, found that TB-related deaths in Ireland were 50% higher than in England or Scotland. The vast majority of TB-related deaths in Ireland occurred among the poorer classes. This updated a 1903 study by Dr John Lumsden.

Poverty was perpetuated in Dublin by the lack of work for unskilled workers, who lacked any form of representation before trade unions were founded. These unskilled workers often had to compete with one another for work every day, the job generally going to whoever agreed to work for the lowest wages. The hiring was done in pubs, resulting in alcoholism – if you didn't take drink with the foreman, and buy him drink, you would not be hired.

James Larkin, the main protagonist on the side of the workers in the dispute, was a docker in Liverpool and a union organiser. In 1907, he was sent to Belfast as local organiser of the British-based National Union of Dock Labourers (NUDL). While in Belfast, Larkin organised a strike of dock and transport workers. It was also in Belfast that Larkin began to use the tactic of the sympathetic strike, in which workers, who were not directly involved in an industrial dispute with employers, would go on strike in support of other workers who were. The Belfast strike was moderately successful and boosted Larkin's standing among Irish workers. However, his tactics were highly controversial and, as a result, Larkin was transferred to Dublin.

...

Wikipedia