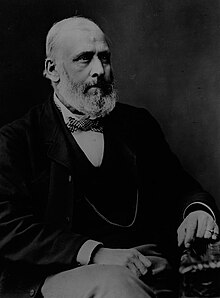

Thorold Rogers

| Thorold Rogers | |

|---|---|

|

|

| Born | 23 March 1823 West Meon, Hampshire |

| Died | 14 October 1890 (aged 67) Oxford |

| Nationality | English |

| Field | Political Economy |

| School or tradition |

English historical school |

| Alma mater |

King's College London University of Oxford |

James Edwin Thorold Rogers (23 March 1823 – 14 October 1890), known as Thorold Rogers, was an English economist, historian and Liberal politician who sat in the House of Commons from 1880 to 1886. He deployed historical and statistical methods to analyse some of the key economic and social questions in Victorian England. As an advocate of free trade and social justice he distinguished himself from some others within the English Historical School.

Rogers was born at West Meon, Hampshire the son of George Vining Rogers and his wife Mary Ann Blyth, daughter of John Blyth. He was educated at King's College London and Magdalen Hall, Oxford. After taking a first-class degree in 1846, he received his MA in 1849 from Magdalen and was ordained. A High Church man, he was curate of St. Paul's in Oxford, and acted voluntarily as assistant curate at Headington from 1854 to 1858, until his views changed and he turned to politics. Rogers was instrumental in obtaining the Clerical Disabilities Relief Act, of which he was the first beneficiary, becoming the first man to legally withdraw from his clerical vows in 1870.

For some time the classics were the chief field of his activity. He devoted himself to classical and philosophical tuition in Oxford with success, and his publications included an edition of Aristotle's Ethics (in 1865).

The Victorian journalist George W. E. Russell (1953–1919) relates an exchange between Rogers and Benjamin Jowett (Fifteen Chapters of Autobiography, 1914, 111–2) :

'Another of our Professors – J. E. Thorold Rogers – though perhaps scarcely a celebrity, was well known outside Oxford, partly because he was the first person to relinquish the clerical character under the Act of 1870, partly because of his really learned labours in history and economics, and partly because of his Rabelaisian humour. He was fond of writing sarcastic epigrams, and of reciting them to his friends, and this habit produced a characteristic retort from Jowett. Rogers had only an imperfect sympathy with the historians of the new school, and thus derided the mutual admiration of Green and Freeman —

...

Wikipedia