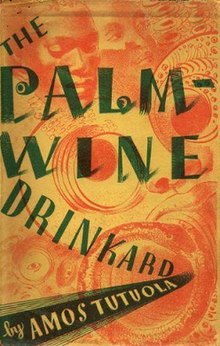

The Palm-Wine Drinkard

First edition (UK)

|

|

| Author | Amos Tutuola |

|---|---|

| Language | English |

| Publisher |

Faber and Faber (UK) Grove Press (US) |

|

Publication date

|

1952 (UK) 1953 (US) |

| Pages | 125 |

| ISBN | |

| Followed by | My Life in the Bush of Ghosts |

The Palm-Wine Drinkard (subtitled "and His Dead Palm-Wine Tapster in the Dead's Town") is a novel published in 1952 by the Nigerian author Amos Tutuola. The first African novel published in English outside of Africa, this quest tale based on Yoruba folktales is written in a modified Yoruba English or Pidgin English. In it, a man follows his brewer into the land of the dead, encountering many spirits and adventures. The novel has always been controversial, inspiring both admiration and contempt among Western and Nigerian critics, but has emerged as one of the most important texts in the African literary canon, translated into over a dozen languages.

The Palm-Wine Drinkard, told in the first person, is about an unnamed man who is addicted to palm wine, which is made from the fermented sap of the palm tree and used in ceremonies all over West Africa. The son of a rich man, the narrator can afford his own tapster (a man who taps the palm tree for sap and then prepares the wine). When the tapster dies, cutting off his supply, the desperate narrator sets off for Dead's Town to try to bring the tapster back. He travels through a world of magic and supernatural beings, surviving various tests and finally gains a magic egg with never-ending palm wine.

The Palm-Wine Drinkard was widely reviewed in Western publications when it was published by Faber and Faber. In 1975, the Africanist literary critic Bernth Lindfors produced an anthology of all the reviews of Tutuola's work published to date. The first review was a rave from Dylan Thomas, the Welsh poet who would die the following year of alcoholism and whose lyrical 500-word review of the drinker’s tale drew attention to Tutuola’s work and set the tone for succeeding criticism. Thomas's own imagery and folkloric grounding seems to have given him a special ear for Tutuola’s novel, saying it was "simply and carefully described" in "young English." Indeed, as Tutuola’s was the first African novel published in English outside of the continent, Thomas can be said to have launched the literary criticism of the Anglophone African novel in the West.

The early reviewers after Thomas, however, consistently described the book as "primitive," "primeval," "naïve," "un-willed," "lazy," and "barbaric" or "barbarous." The New York Times Book Review was typical in describing Tutuola as "a true primitive" whose world had "no connection at all with the European rational and Christian traditions," adding that Tutuola was "not a revolutionist of the word, …not a surrealist" but an author with an "un-willed style" whose text had "nothing to do with the author’s intentions." The New Yorker took this prejudice to its logical ends, stating that Tutuola was “being taken a great deal too seriously” as he is just a “natural storyteller" with a "lack of inhibition" and an "uncorrupted innocence" whose text was not new to anyone who had been raised on "old-fashioned nursery literature." The reviewer concluded that American authors should not imitate Tutuola, as "it would be fatal for a writer with a richer literary inheritance." In The Spectator, Kingsley Amis called the book an "unfathomable African myth," but credited it with a "unique grotesque humour" that is a "severe test" for the reader.

...

Wikipedia