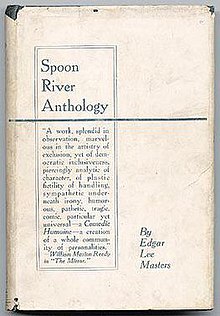

Spoon River Anthology

Macmillan & Co., First edition, frontispiece to Spoon River Anthology.

|

|

| Author | Edgar Lee Masters |

|---|---|

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Genre | Poetry |

| Publisher | William Marion Reedy (1914 & 1915), Macmillan & Co. (1915 & 1916) |

|

Publication date

|

April 1915 |

Spoon River Anthology (1915), by Edgar Lee Masters, is a collection of short, free verse poems that collectively narrates the epitaphs of the residents of Spoon River, a fictional small town named after the real Spoon River that ran near Masters' home town. The aim of the poems is to demystify the rural, small town American life. The collection includes two hundred and twelve separate characters, all providing two-hundred forty-four accounts of their lives, losses, and manner of death. Many of the poems contain cross-references that create an unabashed tapestry of the community. The poems were originally published in the magazine Reedy's Mirror.

The first poem serves as an introduction:

"The Hill"

Where are Elmer, Herman, Bert, Tom and Charley,

The weak of will, the strong of arm, the clown, the boozer, the fighter?

All, all are sleeping on the hill.

One passed in a fever,

One was burned in a mine,

One was killed in a brawl,

One died in a jail,

One fell from a bridge toiling for children and wife—

All, all are sleeping, sleeping, sleeping on the hill.

Where are Ella, Kate, Mag, Lizzie and Edith,

The tender heart, the simple soul, the loud, the proud, the happy one?—

All, all are sleeping on the hill.

One died in shameful child-birth,

One of a thwarted love,

One at the hands of a brute in a brothel,

One of a broken pride, in the search for heart’s desire;

One after life in far-away London and Paris

Was brought to her little space by Ella and Kate and Mag—

All, all are sleeping, sleeping, sleeping on the hill.

Where are Uncle Isaac and Aunt Emily,

And old Towny Kincaid and Sevigne Houghton,

And Major Walker who had talked

With venerable men of the revolution?—

All, all are sleeping on the hill.

They brought them dead sons from the war,

And daughters whom life had crushed,

And their children fatherless, crying—

All, all are sleeping, sleeping, sleeping on the hill.

Where is Old Fiddler Jones

Who played with life all his ninety years,

Braving the sleet with bared breast,

Drinking, rioting, thinking neither of wife nor kin,

Nor gold, nor love, nor heaven?

Lo! he babbles of the fish-frys of long ago,

Of the horse-races of long ago at Clary’s Grove,

Of what Abe Lincoln said

One time at Springfield.

Each following poem is an autobiographical epitaph of a dead citizen, delivered by the dead themselves. They speak about the sorts of things one might expect: some recite their histories and turning points, others make observations of life from the outside, and petty ones complain of the treatment of their graves, while few tell how they really died. Speaking without reason to lie or fear the consequences, they construct a picture of life in their town that is shorn of façades. The interplay of various villagers — e.g. a bright and successful man crediting his parents for all he's accomplished, and an old woman weeping because he is secretly her illegitimate child — forms a gripping, if not pretty, whole.

...

Wikipedia