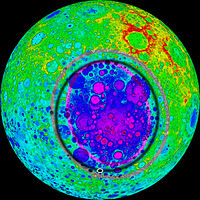

South Pole-Aitken Basin

Topographical map of the South Pole–Aitken basin based on Kaguya data. Red represents high elevation, purple represents low elevation. The purple and grey elliptical rings trace the inner and outer walls of the basin. (The black ring is an old artifact of the image.)

|

|

| Coordinates | 53°S 169°W / 53°S 169°WCoordinates: 53°S 169°W / 53°S 169°W |

|---|---|

| Diameter | About 2,500 kilometres (1,600 mi) |

| Depth | About 13 kilometres (8.1 mi) |

| Eponym |

Lunar south pole Aitken (crater) |

The South Pole–Aitken basin is a huge impact crater on the far side of the Moon. Roughly 2,500 kilometres (1,600 mi) in diameter and 13 kilometres (8.1 mi) deep, it is one of the largest known impact craters in the Solar System. It is the largest, oldest and deepest basin recognized on the Moon. It was named for two features on opposing sides; the crater Aitken on the northern end and the southern lunar pole at the other end. The outer rim of this basin can be seen from Earth as a huge chain of mountains located on the lunar southern limb, sometimes called "Leibnitz mountains", although this name has not been considered official by the International Astronomical Union.

The existence of a giant far side basin was suspected as early as 1962 based on early probe images (namely Luna 3 and Zond 3), but it was not until the acquisition of global photography by the Lunar Orbiter program in the mid-1960s that geologists recognized its true size. Laser altimeter data obtained during the Apollo 15 and 16 missions showed that the northern portion of this basin was very deep, but since these data were only available along the near-equatorial ground tracks of the orbiting Command and Service Modules, the topography of the rest of the basin remained unknown. The geologic map showing northern half of this basin and with its edge depicted was published in 1978 by the United States Geological Survey. Little was known about the basin until the 1990s, when the spacecraft Galileo and Clementine visited the Moon. Multispectral images obtained from these missions showed that this basin contains more FeO and TiO2 than typical lunar highlands, and hence has a darker appearance. The topography of the basin was mapped in its entirety for the first time using altimeter data and the analysis of stereo image pairs taken during the Clementine mission. Most recently, the composition of this basin has been further constrained by the analysis of data obtained from a gamma-ray spectrometer that was on board the Lunar Prospector mission.

...

Wikipedia