Sir Flinders Petrie

| Flinders Petrie | |

|---|---|

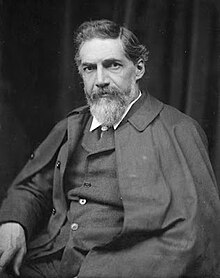

Flinders Petrie, 1903

|

|

| Born |

William Matthew Flinders Petrie 3 June 1853 Charlton, London, England |

| Died | 28 July 1942 (aged 89) Jerusalem, Mandatory Palestine |

| Nationality | British |

| Fields | Egyptologist |

| Known for | Merneptah Stele, pottery seriation |

| Notable awards | Fellow of the Royal Society |

| Spouse | Hilda Petrie |

Sir William Matthew Flinders Petrie, FRS (3 June 1853 – 28 July 1942), commonly known as Flinders Petrie, was an English Egyptologist and a pioneer of systematic methodology in archaeology and preservation of artefacts. He held the first chair of Egyptology in the United Kingdom, and excavated many of the most important archaeological sites in Egypt in conjunction with his wife, Hilda Petrie. Some consider his most famous discovery to be that of the Merneptah Stele, an opinion with which Petrie himself concurred. Petrie developed the system of dating layers based on pottery and ceramic findings.

William Matthew Flinders Petrie was born in Maryon Road, Charlton, Kent, England, the son of William Petrie (1821–1908) and Anne (née Flinders) (1812–1892). Anne was the daughter of Captain Matthew Flinders, surveyor of the Australian coastline, spoke six languages and was an Egyptologist. William Petrie was an electrical engineer who developed carbon arc lighting and later developed chemical processes for Johnson, Matthey & Co.

Petrie was raised in a Christian household (his father being Plymouth Brethren), and was educated at home. He had no formal education. His father taught his son how to survey accurately, laying the foundation for his archaeological career. At the age of eight, he was tutored in French, Latin, and Greek, until he had a collapse and was taught at home. He also ventured his first archaeological opinion aged eight, when friends visiting the Petrie family were describing the unearthing of the Brading Roman Villa in the Isle of Wight. The boy was horrified to hear the rough shovelling out of the contents, and protested that the earth should be pared away, inch by inch, to see all that was in it and how it lay. "All that I have done since," he wrote when he was in his late seventies, "was there to begin with, so true it is that we can only develop what is born in the mind. I was already in archaeology by nature."

...

Wikipedia