Peace of Augsburg

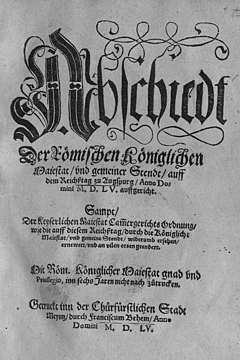

The front page of the document. Mainz, 1555.

|

|

| Date | 1555 |

|---|---|

| Location | Augsburg |

| Participants | Charles V; Schmalkaldic League |

| Outcome | (1) Established the principle Cuius regio, eius religio. (2) Established the principle of reservatum ecclesiasticum. (3) Laid the legal groundwork for two co-existing religious confessions (Catholicism and Lutheranism) in the German-speaking states of the Holy Roman Empire. |

The Peace of Augsburg, also called the Augsburg Settlement, was a treaty between Charles V, Holy Roman Emperor (the predecessor of Ferdinand I) and the Schmalkaldic League, signed on 25 September 1555 at the imperial city of Augsburg. It officially ended the religious struggle between the two groups and made the legal division of Christendom permanent within the Holy Roman Empire, allowing rulers to choose either Lutheranism or Roman Catholicism as the official confession of their state. Calvinism was not allowed until the Peace of Westphalia.

The Peace established the principle Cuius regio, eius religio, which allowed Holy Roman Empire's states' princes to select either Lutheranism or Catholicism within the domains they controlled, ultimately reaffirming the sovereignty they had over their states. Subjects, citizens, or residents who did not wish to conform to the prince's choice were given a period in which they were free to emigrate to different regions in which their desired religion had been accepted.

Charles V had made a provisional ruling on the religious question, the Augsburg Interim of 1548; this offered a temporary ruling on the legitimacy of two religious creeds in the empire, and codified by law on 30 June 1548 upon the insistence of Charles V, who wanted to work out religious differences under the auspices of a general council of the Catholic Church. The Interim reflected largely Catholic principles of religious behavior in its 26 articles, but it did allow for marriage of the clergy, and the giving of both bread and wine to the laity. This led to resistance by the Protestant territories, who proclaimed their own Interim at Leipzig the following year.

The Interim was overthrown in 1552 by the revolt of the Protestant elector Maurice of Saxony and his allies. In the negotiations at Passau in the summer of 1552, even the Catholic princes had called for a lasting peace, fearing the religious controversy would never be settled. The emperor, however, was unwilling to recognize the religious division in Western Christendom as permanent. This document was foreshadowed by the Peace of Passau, which in 1552 gave Lutherans religious freedom after a victory by Protestant armies. Under the Passau document, Charles granted a peace only until the next imperial Diet. The meeting was called in early 1555.

...

Wikipedia