Origins of society

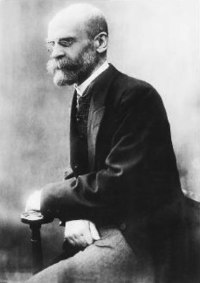

| Émile Durkheim | |

|---|---|

|

The origins of society — the evolutionary emergence of distinctively human social organization — is an important topic within evolutionary biology, anthropology, prehistory and palaeolithic archaeology. While little is known for certain, debates since Hobbes and Rousseau have returned again and again to the philosophical, moral and evolutionary questions posed.

Arguably the most influential theory of human social origins is that of Thomas Hobbes, who in his Leviathan argued that without strong government, society would collapse into Bellum omnium contra omnes — "the war of all against all":

In such condition, there is no place for industry; because the fruit thereof is uncertain: and consequently no culture of the earth; no navigation, nor use of the commodities that may be imported by sea; no commodious building; no instruments of moving, and removing, such things as require much force; no knowledge of the face of the earth; no account of time; no arts; no letters; no society; and which is worst of all, continual fear, and danger of violent death; and the life of man, solitary, poor, nasty, brutish, and short.

Hobbes' innovation was to attribute the establishment of society to a founding 'social contract', in which the Crown's subjects surrender some part of their freedom in return for security.

If Hobbes' idea is accepted, it follows that society could not have emerged prior to the state. This school of thought has remained influential to this day. Prominent in this respect is British archaeologist Colin Renfrew (Baron Renfrew of Kaimsthorn), who points out that the state did not emerge until long after the evolution of Homo sapiens. The earliest representatives of our species, according to Renfrew, may well have been anatomically modern, but they were not yet cognitively or behaviourally modern. For example, they lacked political leadership, large-scale cooperation, food production, organised religion, law or symbolic artefacts. Humans were simply hunter-gatherers, who — much like extant apes — ate whatever food they could find in the vicinity. Renfrew controversially suggests that hunter-gatherers to this day think and socialise along lines not radically different from those of their nonhuman primate counterparts. In particular, he says that they do not "ascribe symbolic meaning to material objects" and for that reason "lack fully developed 'mind.'"

However, hunter-gatherer ethnographers emphasise that extant foraging peoples certainly do have social institutions — notably institutionalised rights and duties codified in formal systems of kinship. Elaborate rituals such as initiation ceremonies serve to cement contracts and commitments, quite independently of the state. Other scholars would add that insofar as we can speak of "human revolutions" — "major transitions" in human evolution — the first was not the Neolithic Revolution but the rise of symbolic culture that occurred toward the end of the Middle Stone Age.

...

Wikipedia