Nerve signal

| Neuron |

|---|

In physiology, an action potential occurs when the membrane potential of a specific axon location rapidly rises and falls: this depolarisation then causes adjacent locations to similarly depolarise. In the original work of HH speed of transmission of an action potential was undefined and it was assumed that adjacent areas became depolarised due to released ion interference with neighbouring channels. Measurements of ion diffusion and radii have since shown this to not be possible. Moreover contradictory measurements of entropy changes and timing disputed the HH as acting alone. More recent work has shown that the HH action potential is not a single entity but is a Coupled Synchronised Oscillating Lipid Pulse (Action potential pulse) powered by entropy from the HH ion exchanges.

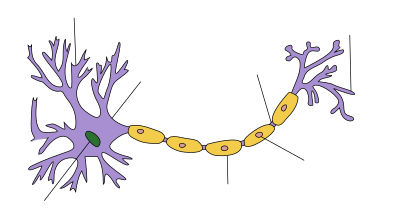

Action potentials occur in several types of animal cells, called excitable cells, which include neurons, muscle cells, and endocrine cells, as well as in some plant cells. In neurons, action potentials play a central role in cell-to-cell communication by providing for (or assisting in, with regard to saltatory conduction) the propagation of signals along the neuron's axon towards boutons at the axon ends which can then connect with other neurons at synapses, or to motor cells or glands. In other types of cells, their main function is to activate intracellular processes. In muscle cells, for example, an action potential is the first step in the chain of events leading to contraction. In beta cells of the pancreas, they provoke release of insulin. Action potentials in neurons are also known as "nerve impulses" or "spikes", and the temporal sequence of action potentials generated by a neuron is called its "spike train". A neuron that emits an action potential is often said to "fire".

Action potentials are generated by special types of voltage-gated ion channels embedded in a cell's plasma membrane. These channels are shut when the membrane potential is near the (negative) resting potential of the cell, but they rapidly begin to open if the membrane increases to a precisely defined threshold voltage, depolarising the transmembrane potential. When the channels open they allow an inward flow of sodium ions, which changes the electrochemical gradient, which in turn produces a further rise in the membrane potential. This then causes more channels to open, producing a greater electric current across the cell membrane, and so on. The process proceeds explosively until all of the available ion channels are open, resulting in a large upswing in the membrane potential. The rapid influx of sodium ions causes the polarity of the plasma membrane to reverse, and the ion channels then rapidly inactivate. As the sodium channels close, sodium ions can no longer enter the neuron, and then they are actively transported back out of the plasma membrane. Potassium channels are then activated, and there is an outward current of potassium ions, returning the electrochemical gradient to the resting state. After an action potential has occurred, there is a transient negative shift, called the afterhyperpolarization.

...

Wikipedia