Nathaniel Shaler

| Nathaniel Southgate Shaler | |

|---|---|

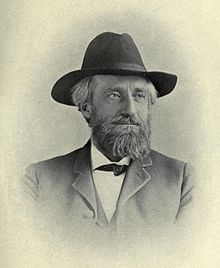

Nathaniel Shaler in 1894.

|

|

| Born |

February 20, 1841 Newport, Kentucky |

| Died | April 10, 1906 (aged 65) Cambridge, Massachusetts |

| Nationality | American |

| Fields | Paleontology, Geology |

| Institutions | Lawrence Scientific School |

| Alma mater | Harvard College |

| Doctoral advisor | Louis Agassiz |

| Signature | |

Nathaniel Southgate Shaler (February 20, 1841, Newport, Kentucky – April 10, 1906, Cambridge, Massachusetts) was an American paleontologist and geologist who wrote extensively on the theological and scientific implications of the theory of evolution.

Born in 1841, Shaler studied at Harvard College's Lawrence Scientific School under Louis Agassiz. After graduating in 1862, Shaler went on to become a Harvard fixture in his own right, as lecturer (1868), professor of paleontology for two decades (1869–1888) and as professor of geology for nearly two more (1888–1906). Beginning in 1891, he was dean of the Lawrence School. Shaler was appointed director of the Kentucky Geological Survey in 1873, and devoted a part of each year until 1880 to that work. In 1884 he was appointed geologist to the U.S. Geological Survey in charge of the Atlantic division. He was commissioner of agriculture for Massachusetts at different times, and was president of the Geological Society of America in 1895. He also served two years as a Union officer in the American Civil War.

Early in his professional career Shaler was broadly a creationist and anti-Darwinist. This was largely out of deference to the brilliant but old-fashioned Agassiz, whose patronage served Shaler well in ascending the Harvard ladder. When his own position at Harvard was secure, Shaler gradually accepted Darwinism in principle but viewed it through a neo-Lamarckian lens. Shaler extended Charles Darwin's work of the importance of earthworm soil bioturbation to soil formation to other animals, such as ants. Like many other evolutionists of the time, Shaler incorporated basic tenets of natural selection—chance, contingency, opportunism—into a picture of order, purpose and progress in which characteristics were inherited through the efforts of individual organisms.

...

Wikipedia