Man's Favorite Sport?

| Man's Favorite Sport? | |

|---|---|

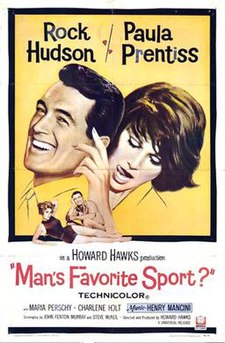

original theatrical release poster

|

|

| Directed by | Howard Hawks |

| Produced by | Howard Hawks |

| Written by | Pat Frank (story) John Fenton Murray Steve McNeil |

| Starring |

Rock Hudson Paula Prentiss Maria Perschy Charlene Holt |

| Music by | Henry Mancini |

| Cinematography | Russell Harlan |

| Edited by | Stuart Gilmore |

| Distributed by | Universal Pictures |

|

Release date

|

|

|

Running time

|

120 min. |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Box office | $6,000,000 |

Man's Favorite Sport? is a 1964 comedy film starring Rock Hudson and Paula Prentiss. Released by Universal Pictures, the movie was directed and produced by Howard Hawks.

Hawks intended this movie to be a homage to his own 1938 screwball classic Bringing Up Baby with Katharine Hepburn and Cary Grant, and unsuccessfully tried to get the original stars to reprise their roles.

Roger Willoughby is a well-known fishing expert who works as a salesman for Abercrombie & Fitch Co. Abigail Page is a brash and flighty public relations woman. Page is determined to secure Willoughby's participation in a prestigious fishing tournament, only to discover that Willoughby is a phony—he's never fished in his life.

By threatening to reveal his secret, Abigail forces Roger to fake his way through the tournament. Willoughby proves himself to be supremely inept: he cannot fish, cannot set up a tent, cannot run or even board a motorboat. He cannot even swim, as he demonstrates by toppling or plunging straight to the lakebed each time he ventures to go fishing.

In the vein of the screwball genre, the dialog is fast and overlapping, the humor broad and slapstick, multiple levels of deception abound, and a decidedly adversarial relationship constantly teeters on the edge of romance.

Upon its release on February 5, 1964, Man's Favorite Sport? performed acceptably but not exceptionally. The film grossed $6 million at the box office, earning $3,000,000 in US theatrical rentals. It was the 24th highest grossing film of 1964. The critics' reactions were somewhat tepid, particularly in comparison to Hawks' earlier works, though Molly Haskell wrote a glowing analysis of the picture seven years later in The Village Voice. Haskell admitted an indifference to the film in 1964, and that upon revisiting the film in 1971 she was "both delighted and deeply moved by the film—delighted by the grace and real humor with which the story was told, and moved by the reverberation of the whole substratum of meaning, of sexual antagonism, desire, and despair."

...

Wikipedia