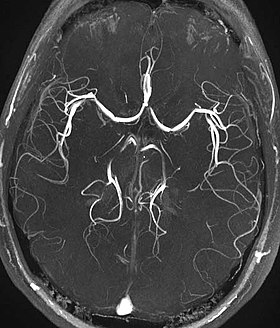

Magnetic resonance angiogram

| Magnetic resonance angiography | |

|---|---|

Time-of-flight MRA at the level of the Circle of Willis.

|

|

| MeSH | D018810 |

| OPS-301 code | 3-808, 3-828 |

| MedlinePlus | 007269 |

Magnetic resonance angiography (MRA) is a group of techniques based on magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) to image blood vessels. Magnetic resonance angiography is used to generate images of arteries (and less commonly veins) in order to evaluate them for stenosis (abnormal narrowing), occlusions, aneurysms (vessel wall dilatations, at risk of rupture) or other abnormalities. MRA is often used to evaluate the arteries of the neck and brain, the thoracic and abdominal aorta, the renal arteries, and the legs (the latter exam is often referred to as a "run-off").

A variety of techniques can be used to generate the pictures of blood vessels, both arteries and veins, based on flow effects or on contrast (inherent or pharmacologically generated). The most frequently applied MRA methods involve the use intravenous contrast agents, particularly those containing gadolinium to shorten the T1 of blood to about 250 ms, shorter than the T1 of all other tissues (except fat). Short-TR sequences produce bright images of the blood. However, many other techniques for performing MRA exist, and can be classified into two general groups: 'flow-dependent' methods and 'flow-independent' methods.

One group of methods for MRA is based on blood flow. Those methods are referred to as flow dependent MRA. They take advantage of the fact that the blood within vessels is flowing to distinguish the vessels from other static tissue. That way, images of the vasculature can be produced. Flow dependent MRA can be divided into different categories: There is phase-contrast MRA (PC-MRA) which utilizes phase differences to distinguish blood from static tissue and time-of-flight MRA (TOF MRA) which exploits that moving spins of the blood experience fewer excitation pulses than static tissue, e.g. when imaging a thin slice.

Time-of-flight (TOF) or inflow angiography, uses a short echo time and flow compensation to make flowing blood much brighter than stationary tissue. As flowing blood enters the area being imaged it has seen a limited number of excitation pulses so it is not saturated, this gives it a much higher signal than the saturated stationary tissue. As this method is dependent on flowing blood, areas with slow flow (such as large aneurysms) or flow that is in plane of the image may not be well visualized. This is most commonly used in the head and neck and gives detailed high-resolution images.

...

Wikipedia