Libellus responsionum

| Libellus responsionum | |

|---|---|

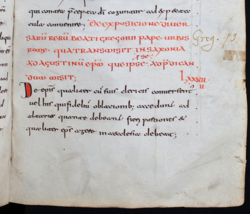

The beginning of the Libellus responsionum in an eighth-century canon law manuscript (Stuttgart, Württembergische Landesbibliothek, HB VI 113, fol. 166r)

|

|

| Full title | Libellus responsionum |

| Also known as | Responsiones; Responsa; JE 1843; "Per dilectissimos filios meos" |

| Author(s) | Pope Gregory I |

| Language | Latin |

| Date | ca 601 |

| Authenticity | presumed authentic |

| Manuscript(s) | over 150 |

| Principal manuscript(s) | Brussels, Bibliothèque royale Albert 1er, MS 10127–44 (363); Cologne, Erzbischöfliche Diözesan- und Dombibliothek, Codex 91; Copenhagen, Kongelige Bibliotek, Gl. kgl. Sam. 1595 (4°); Milan, Biblioteca Ambrosiana, S.33 sup.; Munich, Bayerische Staatsbibliothek, Clm 14780, fols 1–53; Paris, Bibliothèque nationale, Lat. 1603; Paris, Bibliothèque nationale, Lat. 3846; Paris, Bibliothèque nationale, Lat. 12444 ; Prague, Knihovna metropolitní kapituli, O. LXXXIII (1668), fols 131–45; Stuttgart, Württembergische Landesbibliothek, HB.VI.113; Vienna, Österreichische Nationalbibliothek, Codex lat. 2195, ff. 2v–46 |

The Libellus responsionum (Latin for "little book of answers") is a papal letter (also known as a papal rescript or decretal) written in 601 by Pope Gregory I to Augustine of Canterbury in response to several of Augustine's questions regarding the nascent church in Anglo-Saxon England. The Libellus was reproduced in its entirety by Bede in his Historia ecclesiastica gentis Anglorum, whence it was transmitted widely in the Middle Ages, and where it is still most often encountered by students and historians today. Before it was ever transmitted in Bede's Historia, however, the Libellus circulated as part of several different early medieval canon law collections, often in the company of texts of a penitential nature.

The authenticity of the Libellus (notwithstanding Boniface's suspicions, on which see below) was not called into serious question until the mid-twentieth century, when several historians forwarded the hypothesis that the document had been concocted in England in the early eighth century. It has since been shown, however, that this hypothesis was based on incomplete evidence and historical misapprehensions. In particular, twentieth-century scholarship focused on the presence in the Libellus of what appeared to be an impossibly lax rule regarding consanguinity and marriage, a rule that (it was thought) Gregory could not possibly have endorsed. It is now known that this rule is not in fact as lax as historians had thought, and moreover that the rule is fully consistent with Gregory's style and mode of thought. Today, Gregory I's authorship of the Libellus is generally accepted. The question of authenticity aside, manuscript and textual evidence indicates that the document was being transmitted in Italy by perhaps as early as the beginning of the seventh century (i.e. shortly after Gregory I's death in 604), and in England by the end of the same century.

The Libellus is a reply by Pope Gregory I to questions posed by Augustine of Canterbury about certain disciplinary, administrative, and sacral problems he was facing as he tried to establish a bishopric amongst the Kentish people following the initial success of the Gregorian mission in 596. Modern historians, including Ian Wood and Rob Meens, have seen the Libellus as indicating that Augustine had more contact with native British Christians than is indicated by Bede's narrative in the Historia Ecclesia. Augustine's original questions would have been sent to Rome around 598, but Gregory's reply was delayed some years due to illness, and was not composed until perhaps the summer of 601. The Libellus may have been brought back to Augustine by Laurence and Peter, along with letters to the king of Kent and his wife and other items for the mission. However, some scholars have pointed out that the Libellus may in fact never have reached its intended recipient (Augustine) in Canterbury. Paul Meyvaert, for example, has noted that no early Anglo-Saxon copy of the Libellus survives that is earlier than Bede's Historia ecclesiastica (ca 731), and Bede's copy appears to derive not from a Canterbury file copy but rather from a Continental canon law collection. This would be strange had the letter arrived in Canterbury in the first place. A document as important to the fledgling mission and to the history of the Canterbury church as the Libellus is likely to have been protected and preserved quite carefully by Canterbury scribes; yet this seems not to have been the case. Meyvaert therefore suggested that the Libellus may have been waylaid on its journey north in 601 from Rome to England, and only later arrived in England, long after Augustine's death. This theory is supported well by the surviving manuscript and textual evidence, which strongly suggests that the Libellus circulated widely on the Continent for perhaps nearly a century before finally arriving in England (see below). Still, the exact time, place, and vector by which the Libellus arrived in England and fell into Bede's hands is still far from certain, and scholars continue to explore these questions.

...

Wikipedia