Irish potato famine

|

Great Famine an Gorta Mór |

|

|---|---|

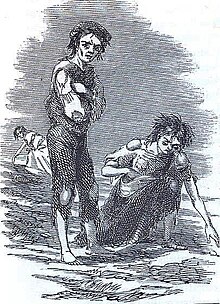

Scene at Skibbereen during the Great Famine, by Cork artist James Mahony (1810–1879), commissioned by The Illustrated London News, 1847.

|

|

| Country | United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland |

| Location | Ireland |

| Period | 1845–1852 |

| Total deaths | 1 million |

| Observations | Policy failure, potato blight, Corn Laws |

| Relief | see below |

| Impact on demographics | Population fell by 20–25% due to mortality and emigration |

| Consequences | Permanent change in the country's demographic, political and cultural landscape |

| Website | See List of memorials to the Great Famine |

| Preceded by | Irish Famine (1740–41) (Bliain an Áir) |

| Succeeded by | Irish Famine, 1879 (An Gorta Beag) |

The Great Famine (Irish: an Gorta Mór, [anˠ ˈgɔɾˠt̪ˠa mˠoːɾˠ]) or the Great Hunger was a period of mass starvation, disease, and emigration in Ireland between 1845 and 1852. It is sometimes referred to, mostly outside Ireland, as the Irish Potato Famine, because about two-fifths of the population was solely reliant on this cheap crop for a number of historical reasons. During the famine, approximately one million people died and a million more emigrated from Ireland, causing the island's population to fall by between 20% and 25%.

The proximate cause of famine was potato blight, which ravaged potato crops throughout Europe during the 1840s. However, the impact in Ireland was disproportionate, as one third of the population was dependent on the potato for a range of ethnic, religious, political, social, and economic reasons, such as land acquisition, absentee landlords, and the Corn Laws, which all contributed to the disaster to varying degrees and remain the subject of intense historical debate.

The famine was a watershed in the history of Ireland, which was then part of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland. The famine and its effects permanently changed the island's demographic, political, and cultural landscape. For both the native Irish and those in the resulting diaspora, the famine entered folk memory and became a rallying point for Home Rule and independence movements. The already strained relations between many Irish and the British Crown soured further, heightening ethnic and sectarian tensions, and boosting Irish nationalism and republicanism in Ireland and among Irish emigrants in the United States and elsewhere.

...

Wikipedia