High Treason (1951 film)

| High Treason | |

|---|---|

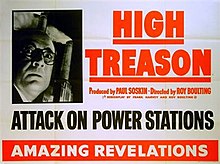

Original British quad poster

|

|

| Directed by | Roy Boulting |

| Produced by | Paul Soskin |

| Written by |

Roy Boulting Frank Harvey |

| Starring |

Liam Redmond Anthony Bushell André Morell |

| Music by | John Addison |

| Cinematography | Gilbert Taylor |

| Edited by | Max Benedict |

| Distributed by | Peacemaker Pictures |

|

Release date

|

|

|

Running time

|

90 minutes |

| Country | United Kingdom |

| Language | English |

| Box office | £88,000 |

High Treason is a 1951 British espionage thriller. It is a sequel to the Oscar-winning 1950 film Seven Days to Noon. Director Roy Boulting, co-director (with his brother John) and co-writer of the first film also directed and co-wrote this one.Frank Harvey, Boulting's co-writer, was also a co-writer of the earlier film. André Morell reprises his role as Detective Superintendent Folland of Scotland Yard's Special Branch from the first film, though in High Treason he is subordinate to the head of Special Branch, Commander Robert "Robbie" Brennan, played by Liam Redmond.

Enemy saboteurs infiltrate the industrial suburbs of London, intending to disable three power stations in London and five other stations elsewhere, all strategically located throughout the UK. Their motive is to cripple the British economy and enable subversive forces to insinuate themselves into government. The saboteurs are thwarted, not by counterintelligence agents, but by workaday London police officers.

The New York Times wrote, "it is worthy to note that High Treason travels at a more leisurely pace than Seven Days, but Roy Boulting, who also directed, achieves an equally intelligent handling of the many pieces needed to fit his intricate jigsaw of a plot," and remarked that, "deft direction, crisp dialogue and a generally excellent cast gives High Treason a high polish," concluding that the film is "a taut tale and a pleasure." More recently, Cageyfilms.com wrote, "although the politics of High Treason are as dated as those of Leo McCarey’s My Son John (1952), the location shooting in London and the character details around the periphery of the narrative provide a fascinating documentary portrait of the metropolis just a few years after the war and, as in Sam Fuller’s Pickup on South Street, the ostensible political element can be seen as little more than a MacGuffin on which to hang the narrative. And speaking of MacGuffins, the film has several very well-developed Hitchcockian elements, particularly the pretentious modern music society which serves as a front for the communist plotters and the labyrinthine building which doubles as a tutorial college and secret commie headquarters."

...

Wikipedia