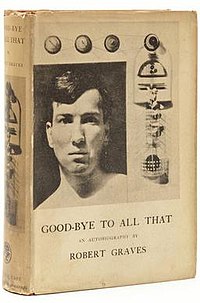

Goodbye to All That

Cover of the first edition

|

|

| Author | Robert Graves |

|---|---|

| Country | United Kingdom |

| Language | English |

| Genre | Autobiography |

| Publisher | Anchor |

|

Publication date

|

1929 1958 (2nd Edition) |

| Media type | Print (hardback & paperback) |

| Pages | 368 (paperback) |

| ISBN | |

| OCLC | 21298973 |

| 821/.912 B 20 | |

| LC Class | PR6013.R35 Z5 1990 |

Good-Bye to All That, an autobiography by Robert Graves, first appeared in 1929, when the author was 34 years old. "It was my bitter leave-taking of England," he wrote in a prologue to the revised second edition of 1957, "where I had recently broken a good many conventions". The title may also point to the passing of an old order following the cataclysm of the First World War; the supposed inadequacies of patriotism, the interest of some in atheism, feminism, socialism and pacifism, the changes to traditional married life, and not least the emergence of new styles of literary expression, are all treated in the work, bearing as they did directly on Graves' life. The unsentimental and frequently comic treatment of the banalities and intensities of the life of a British army officer in the First World War gave Graves fame, notoriety and financial security, but the book's subject is also his family history, childhood, schooling and, immediately following the war, early married life; all phases bearing witness to the "particular mode of living and thinking" that constitute a poetic sensibility.

Laura Riding, Graves' lover, is credited with being a "spiritual and intellectual midwife" to the work.

A large part of the book is taken up by his experience of the First World War, in which Graves served as a lieutenant, then captain in the Royal Welch Fusiliers, with the equally famous Siegfried Sassoon. Good-Bye to All That provides a detailed description of trench warfare, including the tragic incompetence of the Battle of Loos and the bitter fighting in the first phase of the Somme Offensive.

In the Somme engagement, Graves was wounded while leading his men through the cemetery at Bazentin-le-petit church on 20 July 1916. The wound initially appeared so severe that military authorities erroneously reported to his family that he had died. While mourning his death, Graves's family received word from him that he was alive, and put an announcement to that effect in the newspapers.

...

Wikipedia