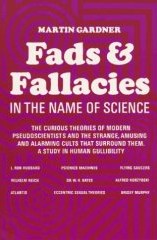

Fads and Fallacies in the Name of Science

The 1957 revised edition

|

|

| Author | Martin Gardner |

|---|---|

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Subject | science, pseudoscience, skepticism, quackery |

| Publisher | Dover Publications |

|

Publication date

|

June 1, 1957, 2nd. ed. |

| Media type | Print (Paperback) |

| Pages | 373 |

| ISBN | |

| OCLC | 18598918 |

| Followed by | Science: Good, Bad and Bogus (1981), Order and Surprise (1983) |

Fads and Fallacies in the Name of Science (1957)—originally published in 1952 as In the Name of Science: An Entertaining Survey of the High Priests and Cultists of Science, Past and Present—was Martin Gardner's second book. A survey of what it described as pseudosciences and cult beliefs, it became a founding document in the nascent scientific skepticism movement. Michael Shermer said of it: "Modern skepticism has developed into a science-based movement, beginning with Martin Gardner's 1952 classic".

The book debunks what it characterises as pseudo-science and the pseudo-scientists who propagate it.

Fads and Fallacies in the Name of Science starts with a brief survey of the spread of the ideas of "cranks" and "pseudo-scientists", attacking the credulity of the popular press and the irresponsibility of publishing houses in helping to propagate these ideas. Cranks often cite historical cases where ideas were rejected which are now accepted as right. Gardner acknowledges that such cases occurred, and describes some of them, but says that times have changed: "If anything, scientific journals err on the side of permitting questionable theses to be published". Gardner acknowledges that "among older scientists ... one may occasionally meet with irrational prejudice against a new point of view", but adds that "a certain degree of dogma ... is both necessary and desirable" because otherwise "science would be reduced to shambles by having to examine every new-fangled notion that came along."

Gardner says that cranks have two common characteristics. The first "and most important" is that they work in almost total isolation from the scientific community. Gardner defines the community as an efficient network of communication within scientific fields, together with a co-operative process of testing new theories. This process allows for apparently bizarre theories to be published — such as Einstein's theory of relativity, which initially met with considerable opposition; it was never dismissed as the work of a crackpot, and it soon met with almost universal acceptance. But the crank 'stands entirely outside the closely integrated channels through which new ideas are introduced and evaluated. He does not send his findings to the recognized journals or, if he does, they are rejected for reasons which in the vast majority of cases are excellent'.

...

Wikipedia