Elaine race riot

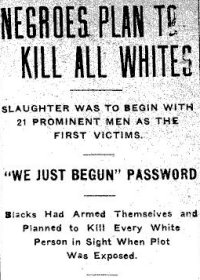

Inflammatory headline in The Gazette (Arkansas), October 3, 1919

|

|

| Date | September 30, 1919 |

|---|---|

| Location | Hoop Spur, Phillips County, Arkansas, U.S. |

| Also known as | Elaine Massacre |

| Participants | residents of Phillips County, Arkansas |

| Deaths | 100–237 blacks, 5 whites |

The Elaine race riot, also called the Elaine massacre, began on September 30–October 1, 1919 at Hoop Spur in the vicinity of Elaine in rural Phillips County, Arkansas. With an estimated 100 to 237 blacks killed, along with five white men, it is considered the deadliest race riot in the state and one of the deadliest racial conflicts in all of United States history. Due to the widespread white mob attacks, in 2015 the Equal Justice Institute classified the black deaths as lynchings in their report on lynchings in the United States.

Located in the Arkansas Delta, the county had been developed for cotton plantations, worked by African-American slaves. In the early 20th century the population was still overwhelmingly black: African Americans outnumbered whites in the area around Elaine by a ten-to-one ratio, and by three-to-one in the county overall. Descendants of slaves, most blacks worked as sharecroppers. White landowners controlled the economic power, selling cotton on their own schedule, running high-priced plantation stores where farmers had to buy seed and supplies, and failing to itemize their settlement of accounts with sharecroppers.

The Progressive Farmers and Household Union of America had organized chapters in the Elaine area in 1918-19. On September 29, representatives met with about 100 black farmers at a church near Elaine to discuss how to obtain fairer settlements. Whites resisted union organizing and often spied on or disrupted such meetings. In a confrontation at the church, two whites were shot, one fatally. The sheriff called a posse and whites gathered to put down a rumored "black insurrection". Other whites entered Phillips County to join the action, making a mob of 500 to 1000 whites. They attacked blacks on sight across the county. The governor called in 500 federal troops, who arrested nearly 260 blacks and were accused of killing some. Over a three-day period, five white men were killed and an estimated 100-240 blacks, with some estimates of more than 800 blacks killed. The events have been subject to debate, especially the total of black deaths.

The only men prosecuted for these events were 122 African Americans, with 73 charged with murder. Twelve were quickly convicted and sentenced to death by all-white juries for murder of the white deputy at the church. Others were convicted of lesser charges and sentenced to prison. During appeals, the death penalty cases were separated. Six convictions (known as the Ware defendants) were overturned at the state level for technical trial details. These six defendants were retried in 1920 and convicted again, but on appeal the state supreme court overturned the verdicts, based on violations of the Due Process Clause and the Civil Rights Act of 1875, due to exclusion of blacks from the juries. The lower courts failed to retry the men within the two years required by Arkansas law, and the defense gained their release in 1923.

...

Wikipedia