Copper poisoning

| Copperiedus | |

|---|---|

|

|

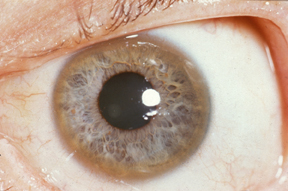

| A Kayser-Fleischer ring, copper deposits found in the cornea, is an indication the body is not metabolizing copper properly. | |

| Classification and external resources | |

| Specialty | emergency medicine |

| ICD-10 | T56.4 |

| ICD-9-CM | 985.8 |

| MedlinePlus | 002496 |

Copper toxicity, also called copperiedus, refers to the consequences of an excess of copper in the body. Copperiedus can occur from eating acid foods cooked in uncoated copper cookware, or from exposure to excess copper in drinking water or other environmental sources.

ICD-9-CM code 985.8 Toxic effect of other specified metals includes acute & chronic copper poisoning (or other toxic effect) whether intentional, accidental, industrial etc.

Copper in the blood and blood stream exists in two forms: bound to ceruloplasmin (85–95%), and the rest "free", loosely bound to albumin and small molecules. Free copper normally reduces oxidative stress, as it is involved in the metabolic elimination of reactive oxygen species, such as with the superoxide radical through Cu-Zn dependent superoxide dismutase. Excessive free copper impairs zinc homeostasis, and vice versa, which in turn impairs antioxidant enzyme function, increasing oxidative stress. Chronically elevated levels of copper intake produces zinc deficiency.

Nutritionally, there is a distinct difference between organic and inorganic copper, according to whether the copper ion is bound to an organic ligand. Organic copper, like that found in food, is a beneficial micronutrient needed for good health. Inorganic metallic copper, like that found in electrical wire, plumbing pipes, brass fittings, redox water filters, sheet metal, cooking utensils, jewelry and pennies, is a neurotoxic heavy metal linked to physical and psychiatric symptoms on par with mercury and lead.

Acute symptoms of copper poisoning by ingestion include vomiting, hematemesis (vomiting of blood), hypotension (low blood pressure), melena (black "tarry" feces), coma, jaundice (yellowish pigmentation of the skin), and gastrointestinal distress. Individuals with glucose-6-phosphate deficiency may be at increased risk of hematologic effects of copper. Hemolytic anemia resulting from the treatment of burns with copper compounds is infrequent.

Chronic (long-term) effects of copper exposure can damage the liver and kidneys. Mammals have efficient mechanisms to regulate copper stores such that they are generally protected from excess dietary copper levels.

...

Wikipedia