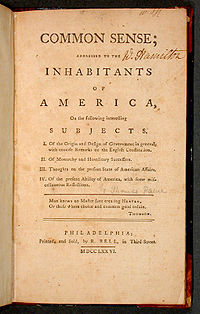

Common sense

Pamphlet's original cover

|

|

| Author | Thomas Paine |

|---|---|

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Published | January 10, 1776 |

| Pages | 48 |

Common Sense is a pamphlet written by Thomas Paine in 1775–76 advocating independence from Great Britain to people in the Thirteen Colonies. Written in clear and persuasive prose, Paine marshaled moral and political arguments to encourage common people in the Colonies to fight for egalitarian government. It was published anonymously on January 10, 1776, at the beginning of the American Revolution, and became an immediate sensation.

It was sold and distributed widely and read aloud at taverns and meeting places. In proportion to the population of the colonies at that time (2.5 million), it had the largest sale and circulation of any book published in American history. As of 2006, it remains the all-time best selling American title, and is still in print today.

Common Sense made public a persuasive and impassioned case for independence, which before the pamphlet had not yet been given serious intellectual consideration. He connected independence with common dissenting Protestant beliefs as a means to present a distinctly American political identity, structuring Common Sense as if it were a sermon. Historian Gordon S. Wood described Common Sense as "the most incendiary and popular pamphlet of the entire revolutionary era".

The text was translated into French by Antoine Gilbert Griffet de Labaume in 1790.

Thomas Paine arrived in the American colonies in November 1774, shortly before the Battles of Lexington and Concord. Though the colonies and Great Britain had commenced hostilities against one another, the thought of independence was not initially entertained. Writing of his early experiences in the colonies in 1778, Paine "found the disposition of the people such, that they might have been led by a thread and governed by a reed. Their attachment to Britain was obstinate, and it was, at that time, a kind of treason to speak against it. Their ideas of grievance operated without resentment, and their single object was reconciliation." Paine quickly engrained himself in the Philadelphia newspaper business, and began writing Common Sense in late 1775 under the working title of Plain Truth. Though it began as a series of letters to be published in various Philadelphia papers, it grew too long and unwieldy to publish as letters, leading Paine to select the pamphlet form.Benjamin Rush recommended the publisher Robert Bell, promising Paine that, where other printers might balk at the content of the pamphlet, Bell would not hesitate nor delay its printing. Bell zealously promoted the pamphlet in Philadelphia's papers, and demand grew so high as to require a second printing. Paine, overjoyed with its success, endeavored to collect his share of the profits and donate them to purchase mittens for General Montgomery's troops, then encamped in frigid Quebec. However, when Paine's chosen intermediaries audited Bell's accounts, they found that the pamphlet actually had made zero profits. Incensed, Paine ordered Bell not to proceed on a second edition, as he had planned several appendices to add to Common Sense. Bell ignored this and began advertising a "new edition". While Bell believed this advertisement would convince Paine to retain his services, it had the opposite effect. Paine secured the assistance of the Bradford brothers, publishers of the Pennsylvania Evening Post, and released his new edition, featuring several appendices and additional writings. Bell began working on a second edition. This set off a month-long public debate between Bell and the still-anonymous Paine, conducted within the pages and advertisements of the Pennsylvania Evening Post, with each party charging the other with duplicity and fraud. Both Paine and Bell published several more editions through the end of their public squabble.

...

Wikipedia