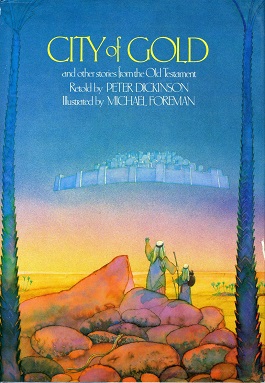

City of Gold (book)

Front cover of 1980 hardcover edition

|

|

| Author | Peter Dickinson |

|---|---|

| Illustrator | Michael Foreman |

| Country | United Kingdom |

| Language | English |

| Genre | Short stories, Bible stories |

| Publisher | Victor Gollancz Ltd |

|

Publication date

|

1980 |

| Media type | Print (hardcover & paperback) |

| Pages | 188 pp (first edition) including bibliography |

| ISBN | |

| OCLC | 472787135 |

| 221.9/505 | |

| LC Class | BS551.2 .D47 1980 |

City of Gold and other stories from the Old Testament is a collection of 33 Old Testament Bible stories retold for children by Peter Dickinson, illustrated by Michael Foreman, and published by Gollancz in 1980. The British Library Association awarded Dickinson his second Carnegie Medal recognising the year's outstanding children's book by a British subject and highly commended Foreman for the companion Kate Greenaway Medal.

City of Gold is a "radical" retelling of Bible stories, according to the retrospective online Carnegie Medal citation. "It is set in a time before the Bible was written down, when its stories were handed from generation to generation by the spoken word."

U.S. editions by Pantheon Books (New York, 1980) and Otter Books (Boston, 1992) retained Foreman's illustrations.

Dickinson described the origin and development of particular story books to the Children's Literature Association when he received the retrospective Phoenix Award for Eva in 2008. With City of Gold, for instance, he was "asked to re-tell the stories of the Old Testament, which I did in the different voices of different people telling the stories for specific purposes while they still existed only in the oral tradition." The request and its deliberate fulfillment place the book near the "commissioned" end of the spectrum. Some others "begin with only what you might call the idea of an idea, a hunch, that there might be a book in them thar hills".

His editor Joanna Goldsworthy at Gollancz made the request, he recalls, for a series of retellings illustrated by Foreman in which fairy tales by Hans Christian Andersen and folk tales collected by the Brothers Grimm had already been done. He declined and argued against the project, because there is no voice today for such retelling and because of the sharp contrast between stories "for amusement with glossy illustrations" and stories still "part of many people's deeply held convictions". But he found the multiple "imagined voices of people who had passionately believed in them." He acknowledges Rudyard Kipling for the technique.

...

Wikipedia