Chilean Civil War

| Chilean Civil War | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

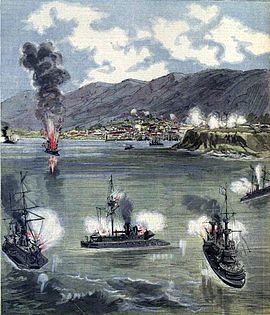

Picture of the rebel fleet attacking Valparaíso, published in Le Petit Journal. |

|||||||

|

|||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

|

||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

José Manuel Balmaceda Juan Williams Rebolledo Manuel Baquedano Orozimbo Barbosa † |

Jorge Montt Ramón Barros Luco Adolfo Holley Emil Körner Estanislao del Canto |

||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 40,000 2 torpedo boats |

1,200 1 monitor 1 armoured frigate 1 cruiser 1 corvette 1 battery ship (January 1891) |

||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| 1 armoured frigate | |||||||

| 5,000 | |||||||

The Chilean Civil War of 1891, also known as Revolution of 1891 was an armed conflict between forces supporting Congress and forces supporting the President, José Manuel Balmaceda. The war saw a confrontation between the Chilean Army and the Chilean Navy, which sided with the president and the congress, respectively. This conflict ended with the defeat of the Chilean Army and the presidential forces and President Balmaceda committing suicide as a consequence. In Chilean historiography the war marks the end of the Liberal Republic and the beginning of the Parliamentary Era.

The Chilean civil war grew out of political disagreements between the president of Chile, José Manuel Balmaceda, and the Chilean congress. In 1889, the congress became distinctly hostile to the administration of President Balmaceda, and the political situation became serious, at times threatened to involve the country in civil war. According to usage and custom in Chile at the time, a minister could not remain in office unless supported by a majority in the chambers. Balmaceda found himself in the difficult position of being unable to appoint any ministers that could control a majority in the senate and chamber of deputies and at the same time be in accordance with his own views of the administration of public affairs. At this juncture, the president assumed that the constitution gave him the power of nominating and maintaining in office any ministers of his choice and that congress had no power to interfere.

The Congress was now only waiting for a suitable opportunity to assert its authority. In 1890, it came to light that President Balmaceda had decided to nominate a close personal friend as his successor. This brought matters to confrontation and the congress refused to approve a budget for supplies to run the government. Balmaceda compromised with congress, agreeing to nominate a cabinet to their liking on condition that the budget would be approved. This cabinet, however, resigned when the ministers understood the full scope of the conflict between the president and congress. Balmaceda then nominated a cabinet not in accord with the views of Congress under Claudio Vicuña, whom it was no secret Balmaceda intended to be his successor. To avoid opposition to his actions, Balmaceda refrained from summoning an extraordinary session of the legislature for the discussion of the estimates of revenue and expenditure for 1891.

...

Wikipedia