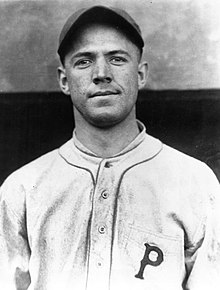

Burleigh Grimes

| Burleigh Grimes | |||

|---|---|---|---|

circa 1916, with Pittsburgh

|

|||

| Pitcher / Manager | |||

|

Born: August 18, 1893 Emerald, Wisconsin |

|||

|

Died: December 6, 1985 (aged 92) Clear Lake, Wisconsin |

|||

|

|||

| MLB debut | |||

| September 10, 1916, for the Pittsburgh Pirates | |||

| Last MLB appearance | |||

| September 20, 1934, for the Pittsburgh Pirates | |||

| MLB statistics | |||

| Win–loss record | 270–212 | ||

| Earned run average | 3.53 | ||

| Strikeouts | 1,512 | ||

| Managerial record | 131–171 | ||

| Winning % | .434 | ||

| Teams | |||

|

As player

As manager |

|||

| Career highlights and awards | |||

|

|||

| Member of the National | |||

|

|

|||

| Inducted | 1964 | ||

| Election Method | Veteran's Committee | ||

As player

As manager

Burleigh Arland Grimes (August 18, 1893 – December 6, 1985) was an American professional baseball player, and the last pitcher officially permitted to throw the spitball. Grimes made the most of this advantage and he won 270 games and pitched in four World Series over the course of his 19-year career. He was elected to the Wisconsin Athletic Hall of Fame in 1954, and to the Baseball Hall of Fame in 1964.

Born in Emerald, Wisconsin, Grimes was the first child of Nick Grimes, a farmer and former day laborer, and the former Ruth Tuttle, the daughter of a former Wisconsin legislator. Having previously played baseball for several local teams, Nick Grimes managed the Clear Lake Yellow Jackets and taught his son how to play the game early in life. Burleigh Grimes also participated in boxing as a child.

He made his professional debut in 1912 for the Eau Claire Commissioners of the Minnesota–Wisconsin League. He played in Ottumwa, Iowa, in 1913 for the Ottumwa Packers in the Central Association.

Grimes played for the Pittsburgh Pirates in 1916 and 1917. Before the 1918 season, he was sent to the Brooklyn Dodgers in a multiplayer trade. When the spitball was banned 97 years ago in 1920, he was named as one of the 17 established pitchers who were allowed to continue to throw the pitch. According to Baseball Digest, the Phillies were able to hit him because they knew when he was throwing the spitter. The Dodgers were mystified about this; first they thought the relative newcomer of a catcher, Hank DeBerry, was unwittingly giving away his signals to the pitcher, so they substituted veteran Zack Taylor, to no avail. They suggested that a spy with binoculars was concealed in the scoreboard in old Baker Bowl in Philadelphia, reading the signals from a distance, but the Phils hit Grimes just as well in Ebbets Field in Brooklyn. A batboy solved the mystery by pointing out that Burleigh's cap was too tight. It sounded silly, but he was right. The tighter cap would wiggle when Grimes flexed his facial muscles to prepare the spitter. He got a cap a half-size larger and the Phillies were on their own after that.

...

Wikipedia